In Melbourne, collaborative development is turning grey streets green

Nightingale Village in Melbourne’s inner north is using the power of the collective to pioneer a potent new model of sustainable urban development.

Brunswick is one of the many places in Melbourne where the abstraction of the city’s rampant population growth figures, the highest in Australia and among the highest in the world, find expression in cold, hard concrete reality.

A suburb in the city’s inner north, it was formerly home to factories, sweatshops and the working class neighbourhoods that kept the cogs of a once-thriving manufacturing economy turning. Now, most of that is gone. Where once were warehouses and workshops are now apartment buildings, built boundary-to-boundary in rows up to eight storeys high. The dominant material is concrete, but glass, cement render and dodgy polystyrene panelling get a good look in too. Greenery? Scant to absent.

Standing in the midst of all this prematurely aging grey, a few blocks south down the train tracks from Brunswick’s Anstey Station, Andy Fergus casts a less-than-appreciative eye over his surroundings.

“In Melbourne, we have a problem where every development goes in and borrows amenity off everyone else until they’re all completely built out. What happens is, with more development, you compound a lower quality environment,” say Fergus. “An effective planning system should perpetuate a condition where every building contributes to a greater whole. It should get better with redevelopment, but every site is set up in contest with every neighbour.”

An urban designer at the City of Melbourne, Fergus is giving me a tour of a neighbourhood that will soon become home to Nightingale Village. This is redevelopment of a radically different ilk, which promises to circumvent the short-sighted opportunism that has, for better or worse, completely transformed this part of the city over the past decade.

Fergus has been consulting on the urban guidelines for Nightingale Village, together with Mark Jacques of the landscape architecture practice Openwork, who joins us on this sortie. The development spans four city blocks, which in private hands is an established inner city site of unusually large scale. The duo, though, don’t describe themselves as master planners, but as “pro-bono agitators”, a term which hints at the strange blend of systematised control and mild anarchy underpinning the Village’s urban vision.

“We’re sort of inventing a new typology of public open space,” says Jacques. “We’re trying to set up a situation where ‘permission is granted’ for agency.”

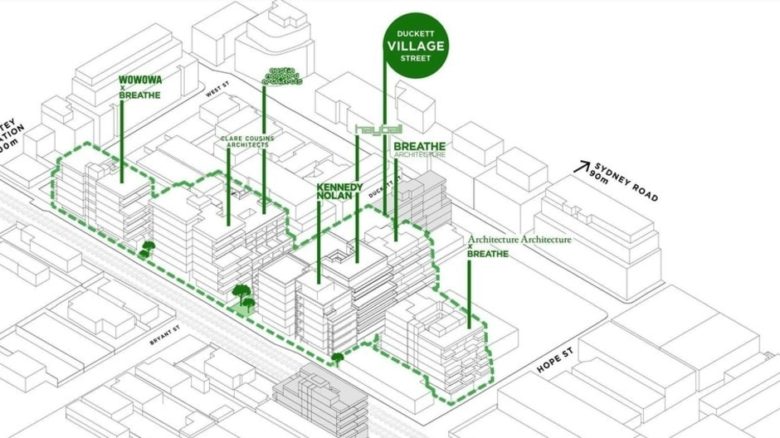

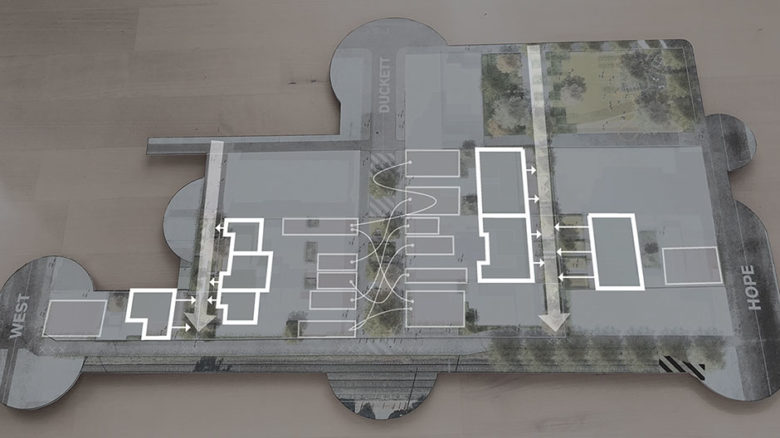

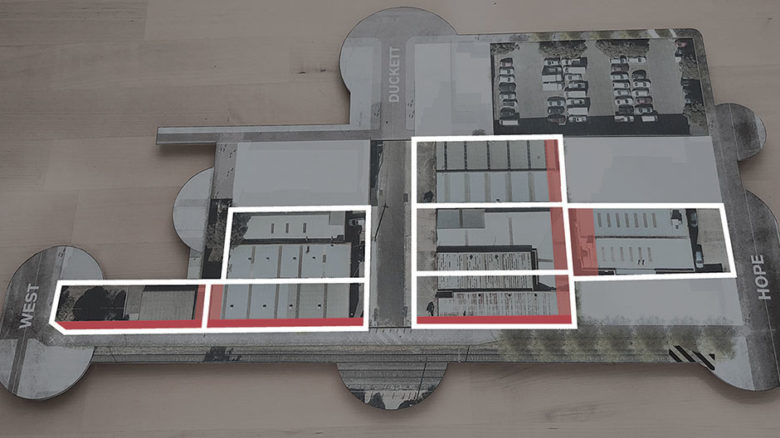

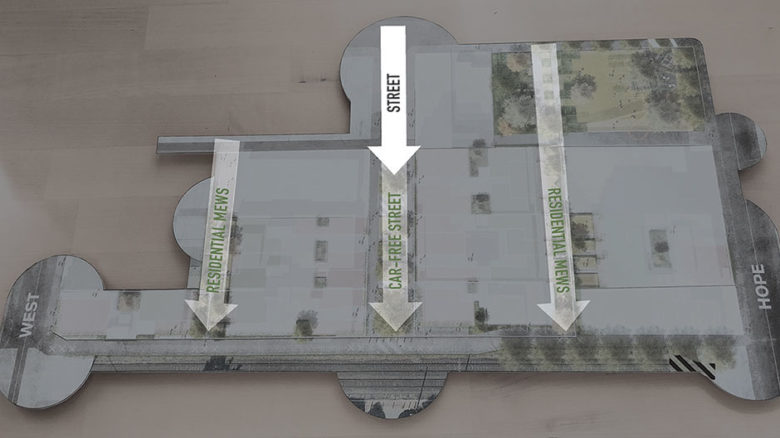

The original plans for Nightingale Village would see seven apartment buildings built across the site, bisected by Duckett Street, which runs from east to west where the edge of the train line and bike path defines the site’s western boundary. In addition to this, though, the plans for the Village will also see two public, pedestrianised ‘mews’ lanes cut through it. Flanking each side of Duckett, the mews will reintroduce connectivity to the train line and bike paths, together with some much needed greenery, light and open space in this chocka-block pocket of Brunswick.

Proposed design for Duckett Street, Nightingale Village. Image: Nightingale Group

A gathering of residents and friends of The Commons and Nightingale 1, Florence Street. Image: Nightingale Group

Proposal sketch for Nightingale Village. Image: Andy Fergus

All of this is very sensible urban planning, improving outlook, light, air and access for the apartment buildings, while adding to the general amenity of the surrounding neighbourhood. Sensible may as well be radical given the recent history of private development in Melbourne (as Fergus alludes, most private developers would have done their best to build the blocks out entirely, thereby ‘maximising’ their potential yields), but there are other elements to the scheme which tilt it more emphatically into unconventional territory.

“The ground level is designed to be porous, where there’s this deliberate ambiguity about where the street begins and how far the public realm pushes in,” says Jacques.

To help cultivate this, the mews will send mixed urban messages, to give the impression of public access to a private space. What Jacques calls the “idea of a threshold”, something like a self-closing small gate, will lend a sense of containment. The goal is to change how people relate to the space, to get both visitors and occupants to see it as partly ‘private’ and in that sense worthy of respect, care, and even inhabitation.

“This is where if you get the armature of the street right – you get a threshold of fence, you seed it with some furniture – then people will do this themselves,” he continues. “So we’re essentially saying that even though that’s public land, we are giving people license to take ownership. Because of that particular set of configurations, you’ll get versions of parklets happening throughout the Village, by all sorts of authors – council, consultants, residents.”

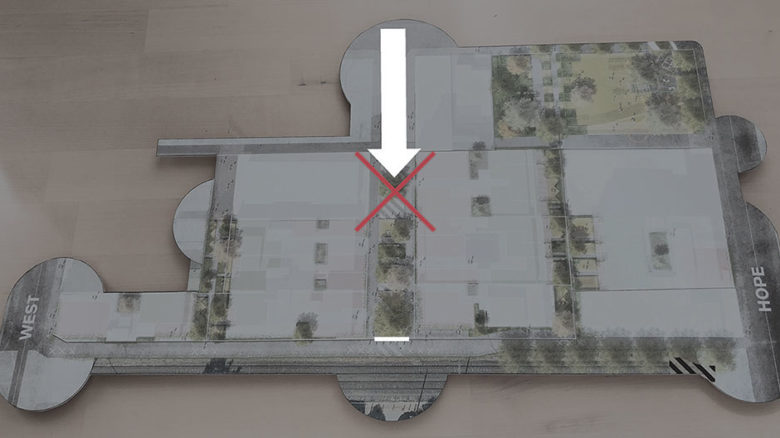

The original plans for Nightingale Village would have seen seven buildings built. The WOWOWA site will now be developed into a public park. Image: Nightingale Group

Nightingale Village original masterplan. Image: Openwork

While most developers might struggle with a concept like ‘ambiguity’ when it comes to private space (profitable! The Greatest!) and public space (COSTLY…), this dynamic isn’t without precedent in Australia – albeit its forerunners developed their fuzzy boundaries more organically than intentionally. Fergus points to Lawson Grove, South Yarra; McElhone Place, Surry Hills; and Northumberland Street, Collingwood.

“These three projects have a good level of architecture, broadly, nothing exceptional, but they have incredible levels of private appropriation of semi-public spaces,” Fergus says. “That comes from a strong sense of community – the definition of space is where the landscape can grow. The architect’s work completed at the edge of the building, and then 50 years of occupation later, people have this incredible care.”

This is not the kind of landscape you could normally have in a civic context, as it requires far too much maintenance. It’s fussy, over-planted, fragile. To survive, it needs people who care about it living in close proximity. As Fergus explains, though, it brings “identity in density” – in taking responsibility for the public realm, the nearby occupants have also made themselves visible within it.

There are other precedents of sorts in the neighbourhood surrounding Nightingale Village, too.

The Village is being built by Nightingale Housing, a development group originally established by Breathe Architecture to deliver triple bottom line apartments at cost. A block north from the edge of the Village site on Florence Street are The Commons apartment building and its cousin, Nightingale 1, the group’s first project.

Designed by Breathe Architecture and built by ethical developer Small Giants, when The Commons opened in 2013, it was an anomaly. The notion of a ‘green’ apartment building was almost completely unheard of in Australia, with sustainable residential architecture mostly confined to private single dwellings.

The Commons followed many of the core design principles of these houses (passive heating and cooling thanks to good orientation, thermal mass and cross ventilation) and it included much of the technological gadgetry often associated with green buildings (solar panels on the roof, hydronic heating, double-glazed windows with thermal breaks, ultra-efficient electrics). What made it especially noteworthy, though, was an interest in engaging with systems beyond the scale of the individual dwelling, and its proposition that the challenges of living sustainably are best tackled collectively.

It demonstrated that 24 units within an inner city apartment building could be more sustainable than 24 isolated single dwellings (and the car travel and additional building materials that go with them). It used a communal laundry on the roof to save space within its apartments, and reduce the environmental impact that plumbing in scores of individual washing machines would otherwise have had. It took advantage of economies of scale to deliver more efficient onsite power generation systems, from solar hot water to photovoltaics, while using collective bargaining strength to negotiate for cheaper power generated offsite.

In what was arguably its most environmentally impactful departure from standard practice at the time, though, it also ditched basement carparking in favour of carshare and the neighbouring bike, tram and train infrastructure (successfully arguing for an exemption from the local council’s carparking requirements for new dwellings in the process).

The Village model represents a dramatic expansion of the systems thinking and ethos behind The Commons and its cousin Nightingale 1 to an urban scale, to compounding effect. As Bonnie Herring, a director at Breathe Architecture, described to Foreground, this ‘super-site’ brings with it collective power far beyond what is possible even with a 24 unit apartment building.

“With The Commons and N1 something special happened. By locating two buildings with like-minded communities opposite one another, the space between buildings – along with the public edges and internal laneways within them – has become a meeting ground,” says Herring. “The street has become the place where the broader community building happens. I can’t wait to see how that effect will amplify at the Village, where the street will be pedestrianized and flanked by five new Nightingale buildings.”

From closed loop organics management and food production, grey water infrastructure, greater economies of scale and efficiency in power generation and purchase, and a considered ecological support infrastructure, there are a raft of potential tools available to the Nightingale Village team and its future occupants in addressing the challenges of sustainable living, especially pronounced now in the face of our rapidly changing climate.

Many of the units within Nightingale Village have a direct residential address. Image: Openwork

Duckett Street within Nightingale Village will be partially pedestrianised and include a small park. Image: Openwork

Nightingale Village has imposed a setback of two metres from the nearby bike path on its buildings. Image: Openwork

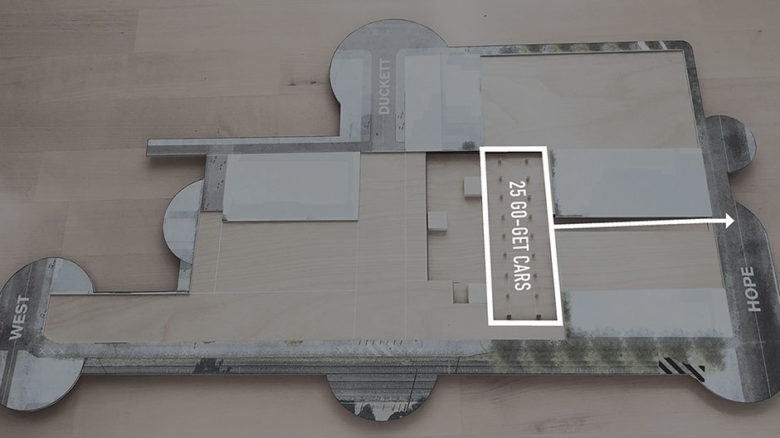

Nightingale Village's share cars are co-located on site. Image: Openwork

Diagram showing hierarchy of streets within Nightingale Village. Image: Openwork

“The public realm and landscape opportunities at the Village are incredible. Overall, the project can take an intimate, human-scaled approach throughout the public ground level that isn’t possible with single building projects,” says Herring. “Meanwhile the extent of landscape we collectively work with – on the ground, on rooftops and creeping up the buildings – will help to cool the area through transpiration and shade. This is most effective at a precinct scale.”

Melbourne is already suffering from increasing temperatures under climate change and the urban heat island effect is especially pronounced in The City of Moreland, which Brunswick forms a part of. It suffers from a surfeit of unshaded concrete and tarmac, and likewise a lack of soil, root systems or even porous surfaces contribute to the area’s problems coping with flash flooding – another phenomena that’s set to get steadily worse under climate change.

Recent development in the surrounding neighbourhood has exacerbated many of these issues, but the Village promises to tip the balance back in favour of a more resilient urban form. It will address some of these problems directly, through greenery, parklets and the partial pedestrianisation of Duckett Street. The City of Moreland, though, has also announced the purchase of one of the Village sites (previously pegged for a building by architects WOWOWA) and some adjacent properties, for a 2600-square-metre park.

This latter alone is a big win for the local community. As the council has it, this is the first time it has ever purchased land specifically for the creation of a new public park.

It’s unclear whether or not this new park would have happened without the support of Nightingale Village, its collective ethos and the momentum behind it, but it’s tempting to think not.

As Herring observes, “Shared areas are often where the magic happens.”

–

Maitiú Ward is a publisher, editor, journalist and occasional broadcaster with a special interest in architecture, design and the city.