Marvellous no more: Melbourne’s planning failure

Melbourne’s growth area planning is failing, says a report by a prominent group of planners and urban design professionals, with stark consequences for Australia’s second largest city.

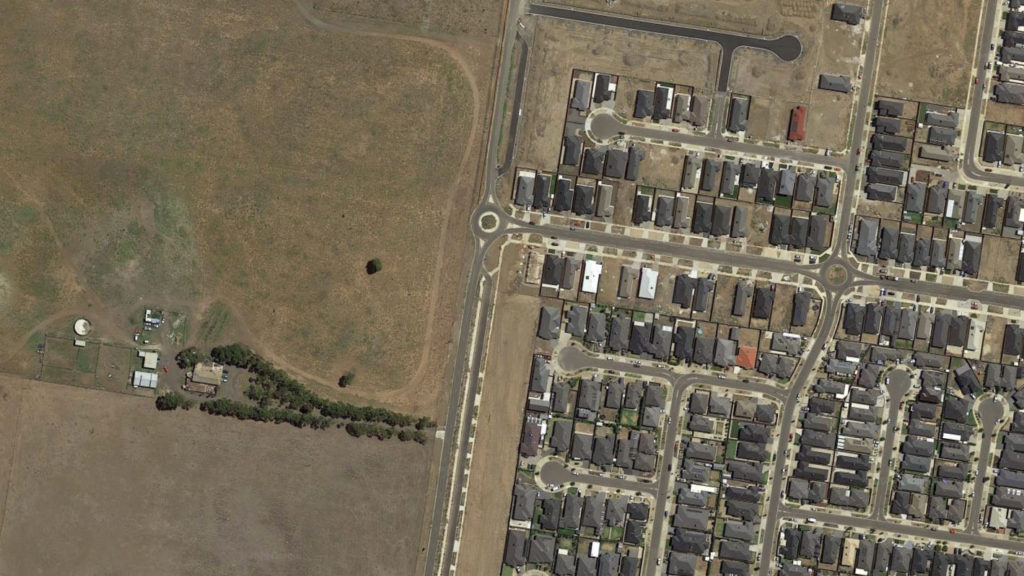

Melbourne, the second largest city in Australia and a key driver of the country’s economy, continues to expand outward at an unprecedented rate. While growth and intensification are being spread across the city, the greatest population increases are still happening in Melbourne’s outer growth corridors. The “new Melbourne” being constructed in these new suburbs has multiple shortcomings, to the extent that we are creating a city likely to fail.

I am part of a group of planners, urban designers, a transport engineer, architects and academics who have been deliberating on Melbourne’s deeply concerning patterns of greenfield development. What started as an informal discussion has developed into an evidence-based report by a group we’re now calling Charter 29. The name refers to the first time Melbourne developed a plan for urban growth, independent of the influence of politicians and the property development lobby—1929.

The quality of our physical, natural and social environments influences our personal wellbeing. Liveable neighbourhoods, defined in terms of attractive environments, increase self-reliance and adjustment while reducing crime, unhealthy lifestyles, anti-social behaviour and the need for social support.

As our report uncovers, in the vast, car-dependent new suburbs now being built on Melbourne’s outer fringe, the lowest income and least tertiary-educated groups endure long journey to work times, a lack of diverse housing choices and Melbourne’s worst services and social and physical infrastructure. Relatively few jobs are available, particularly jobs in the higher income brackets.

The Victorian Planning Authority has just produced new draft Guidelines for Precinct Structure Planning in Melbourne’s greenfields. The guidelines have admirable objectives, but there is no plan for any significant change to the method of development delivery through subdivision and project home building. Regardless, our report demonstrates that even current objectives are largely unmet. This is sadly far from unusual in Melbourne’s recent history, where successive governments have failed to adhere to their own planning objectives and guidelines.

In 2009, the “Transforming Australian Cities” study by City of Melbourne and the Victorian government transport department, suggested that an additional four million new arrivals could be accommodated in medium density development on less than one tenth of the then-existing metropolitan area. This plan proposed increased density close to existing transport and services leaving the remains 90% of the city unchanged.

If the city’s development had followed what this study proposed in 2009, the Victorian government could have saved an estimated $440 billion in infrastructure costs over a period of 50 years. Instead, in the past decade subdivision design has been dominated by detached housing with low population and housing density constructed on single lots. Little consideration has been given to the provision of higher density dwellings close to public transport, parkland and services, or to a gradation of house sizes.

Unsurprisingly, despite massive spending on roads and freeway, the result of this sprawling, low density development mode is that we are now seeing government fail to deliver adequate transport and services in the growth corridors.

Planning for Melbourne has been thoroughly politicised, which has undermined long-term, evidence-based decision-making in the community interest. Since 1971, the city has adopted 10 different strategic plans. In turn, seven different agencies are involved in the city’s planning. No agency has responsibility for balancing dwelling numbers and types constructed in both the established and new suburbs, or for limiting outer urban growth.

The end result is institutional fragmentation and the failure of strategic metropolitan planning. Power has effectively devolved to a deregulated statutory planning system designed to advantage the development industry. This sets up a disastrous future for a city of an estimated eight million people by 2050.

Our group Charter29 believes Melbourne can and must do better than this.

Bruce Echberg is an architect, landscape architect and urban designer who has practiced as a landscape architect and urban designer in Australia since the 1970s. He is one of the members of Charter 29, a group of environment professionals who believe that planning in Victoria is failing. The report this column refers to can be found here.