Inheriting the Western Sydney of tomorrow

There’s much to say about the future of Sydney’s ever-expanding west… but what do the kids say? NSW’s peak youth advocacy body, Youth Action, makes a case for even greater youth participation in Greater Western Sydney’s urban planning.

As the NSW government continues to forecast and plan for ambitious urban and economic growth across Western Sydney, supported through a series of large-scale infrastructure investments, Youth Action considers it critical that government meaningfully engages with young people in those decision-making processes that will impact their lives. This is not only because such processes will undoubtedly deliver better public spaces. Other benefits include both improved social inclusion and education outcomes. To actively engage young people in the decision-making processes that affect them is also not only advisable, it is protected as a fundamental right of young people by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

To this end Youth Action recently lodged a submission to the Greater Sydney Commission (in March 2017) entitled The Future of the Greater West: Young People and Place-making. As a result of this research they proposed the following recommendations to the Greater Sydney Commission.

Recommendation 1: That the Greater Sydney Commission establishes a Youth Peer Engagement Program to build capacity of young people in Western Sydney to increase youth participation in local community and urban design processes.

Recommendation 2: That the Greater Sydney Commission facilitates youth friendly workshops to design and create public spaces that fulfill the needs of young people in the West Central District.

Recommendation 3: That the Greater Sydney Commission develops a detailed framework to embed meaningful youth participation into all district plans, as well as the overarching Social, Economic, and Environmental plans. Recommendation 4: That the Greater Sydney Commission works with existing local resources and networks through service providers and other youth organisations to better engage young people with greater barriers to participation.

The following is an extract from that submission.

Parramatta CBD looking north. Image: Arsene

NDIS workshop Western Sydney. Image: Sunnyfield.

Central Cabramatta. Image: Design for Health

Haldon St, Lakemba.

Sydney Olympic Park train station, Homebush Bay. Image: Adam.J.W.C.

Central Katoomba, sitting on the outer reaches of the Greater Western Sydney area. Image: Adam.J.W.C.

The current state of affairs

Current efforts in community consultation often either excludes youth participation or includes them only in a peripheral or tokenistic manner. This may be due to a lack of specialist understanding of youth participation methodologies among built environment professionals, combined with a reliance on flawed consultation frameworks. One such example is the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2), which is often relied upon for community consultation processes in NSW, and around the world. The reliance upon a framework that inherently excludes young people perpetuates the deficit in youth participation.

Young people are often perceived as apathetic and unwilling to participate in consultations, when the opposite is true; young people are actively looking for ways to contribute, but are met with significant barriers.

Reaching and hearing from young people requires addressing those barriers with a multifaceted approach to community consultation, using traditional participation methods alongside innovative approaches and taking advantage of the networks of young people that already exist in communities. A wide-reaching approach to youth consultation is especially important in uniquely youthful populations like south-west and Western Sydney, which are rich with cultural and linguistic diversity.

A local, community-driven place-making approach may be most effective at meaningfully engaging diverse young voices in these areas. Western Sydney is projected to be the fastest growing area in Australia over the next two decades. The 5-19 year age bracket is forecast to grow by over 50 percent in both the south west and west central districts. Given that young people use public spaces as much, if not more than, other age groups, it is important that areas with significant youth populations are equipped with sufficient and suitable public spaces, where young people can not only safely meet, but also feel a sense of belonging.

Unfortunately, this is not currently the case in Greater Western Sydney. Both the south west and west central districts have a below-average area of public open space compared to Greater Sydney as a whole. This shortfall is particularly severe in the west central district, where public open space makes up just 13 percent of land area, well below the Greater Sydney figure of 56 percent. Additionally, the frequent exclusion of young people from the design process, whether deliberate or not, means that many public spaces are tailored to small children and their parents, to the exclusion of teenagers and young adults.

As a direct product of young people’s exclusion from the design process there is a lack of suitable public spaces. This is problematic, as it has flow-on effects that can lead to social isolation and other issues. When youth-oriented public spaces are not available, young people are forced to meet in other areas, such as car parks and transit interchanges. This often leads to other members of society feeling annoyed or even intimidated by their presence in these areas, perpetuating a negative stigma of young people. This stereotyping of young people can lead to further social exclusion, potentially pushing young people towards antisocial behaviour and reinforcing this cycle of alienation.

Future opportunity

Greater Western Sydney’s many languages and cultures make the region unique and rich, yet it is also these characteristics that compound the existing exclusionary cycle. As ‘the epicentre of Australian migration’, Western Sydney has higher levels of overseas birth, and lower levels of English language proficiency than both Greater Sydney and Australia as a whole. When participatory processes fail to account for diversity, they, in effect, are designed to exclude such communities and exacerbate social isolation. Place-making has a crucial role to play in combating isolation and antisocial behaviour, particularly to build socially cohesive communities in Western Sydney.

The creation of new places or changes to existing conditions undoubtedly impacts the sense of belonging that young people have to an area. That is, ‘…young people’s belonging to a place, a sense of rootedness or a form of place attachment impact on their everyday decisions (e.g. to stay or leave a community).’ A strong connection to place provides young people with avenues to stay connected to the people and places that they care about. This is especially important in the context of the south west and west central districts, where changing populations and supporting infrastructure will undoubtedly change the places in which young people live and belong to. When young people have a greater understanding of local issues and are more actively engaged in their communities, they can also develop skills relating to initiative and entrepreneurship.

Young people should be valued as active citizens of the present, but should also be considered as future leaders. We must recognise the value in nurturing their interests and capabilities particularly in relation to local communities. The capacity-building value of participatory place-making is a notable benefit, particularly in an area like Western Sydney, with lower-than-average levels of formal education attainment.

Not without its challenges

Youth Action acknowledges that the task of engaging a diverse group of young people can prove difficult. Youth populations are often considered ‘hard to reach’, and don’t respond in large numbers through traditional channels of public engagement, such as written submissions, focus groups and town hall meetings. Common barriers to participation include time and financial constraints, as well as less tangible barriers, such as a lack of trust in government processes and insufficient understanding of the planning system.

Successful youth participation in place-making relies on a variety of engagement methods, using traditional consultation processes in combination with current technology and social media, as well as engaging young people through pre-existing youth networks and organisations. The need for a more complex approach to consultation means that projects need dedicated youth consultation processes to meaningfully engage young people and to achieve inclusive and improved community planning and design outcomes.

For example, the West Central draft district plan overview has no specific priorities or actions in relation to engaging young people. The call for social media feedback using the ‘#GreaterSydney’ hashtag may generate some engagement from young people, but given the diversity of the youth cohort in the area and the ‘hard-to-reach’ status of many young people, this approach alone is unlikely to return an accurate representation of local youth sentiment. This is insufficient to overcome the barriers young people experience in contributing to public processes. To ensure meaningful, ongoing youth participation at a local level, the district plans need to draw upon past successes in youth engagement to inform a comprehensive strategy for youth consultation.

There are many case studies that showcase effective examples of meaningful youth engagement in projects relating to place and planning. Their resulting positive community outcomes demonstrate the impact of effective youth engagement in improved public space and the potential to create better outcomes for and with young people overall. The Youth Action submission to the Greater Sydney Commission highlighted three case studies, in Scotland, New South Wales and Western Australia. Of these three we have included the Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza below, as an exemplary achievement in including young people within a major piece of city-building.

The outdoor tennis table at Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza. Image: Luke Thompson

Opening day, Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza.

Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza skate bowl. Image: Luke Thompson

Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza parkour circuit. Image: Luke Thompson

Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza climbing station. Image: Luke Thompson

A parkour enthusiast tries out the circuit on opening day.

The plaza consulted a wide range of people, meaning that young children had participatory activities, too.

The same goes for adolescents on the older end of the 'youth' spectrum.

An aerial view of the park. Image: Luke Thompson

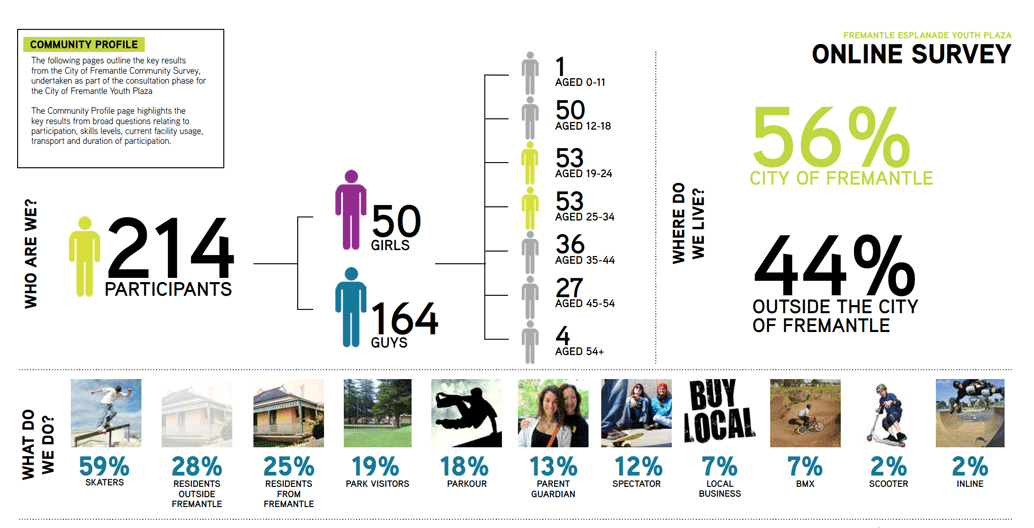

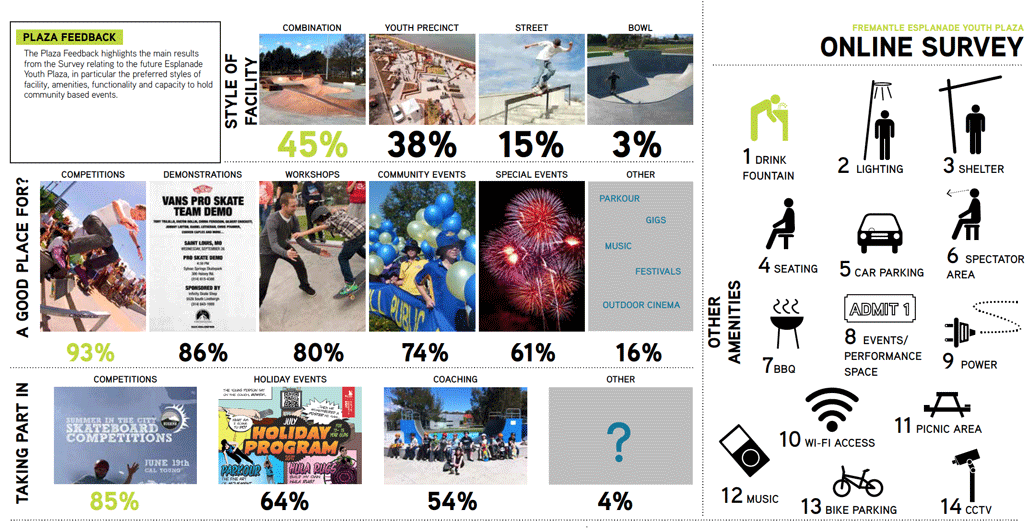

Results from the consultation period.

Results from the consultation period (continued).

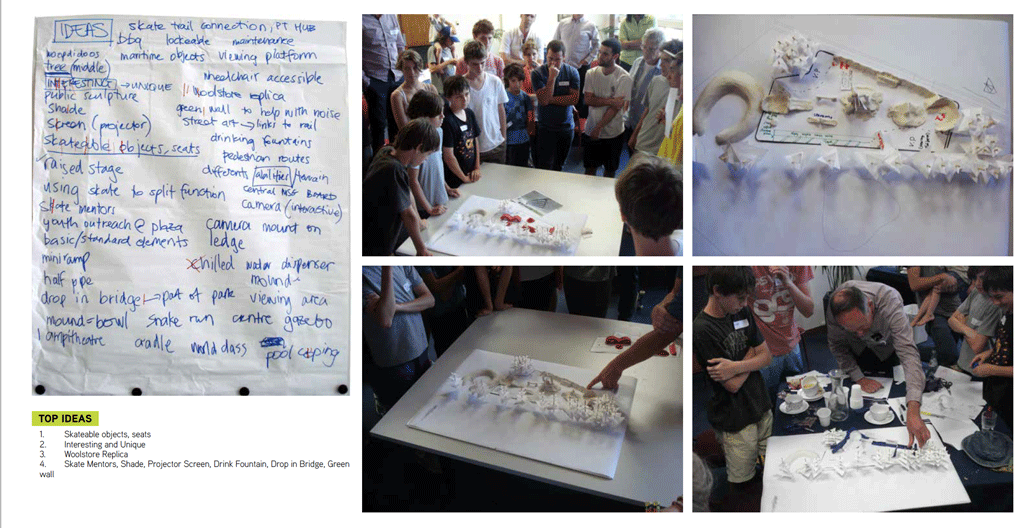

Scenes of the consultation period.

Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza, Western Australia

The Fremantle Esplanade Youth Plaza is a large multi-use public space in the centre of Fremantle, Western Australia. The plaza features a range of youth-oriented recreational facilities including a performance space, a rock climbing wall, a world-class skate park and ping pong tables. The space was designed and built using a combination of state and local government funding. The initial vision for the space was an inclusive, flexible, youth-oriented facility in a central location, with recreational opportunities for families and young people.

The City of Fremantle commissioned Convic Design, an independent design firm with a focus on creating youth-inclusive spaces, to design and conduct a seven-month consultation process on the plaza’s design. This involved two main stages: an initial ‘information gathering’ phase, followed by a series of community workshops. The Council wanted participants in the consultation to represent ‘the diverse community of Fremantle’, but also recognised the need to consult specifically with the future users of the space, many of which would be young skaters.

By giving the plaza’s users a significant say in the design of the space, the consultation process would ‘empower youth’, and encourage young people to ‘take ownership’ of the plaza and ‘become guardians of the space’. The initial stage of the consultation process primarily consisted of an online survey about the site’s design. The survey received over 200 responses, mainly from young people.

Additionally, to engage meaningfully with the future users of the space, the Council hosted a number of skate workshops at local skate parks, and interviewed the participants in the workshops about what they would like to see at the new facility. This not only allowed the interviewers to collect relevant information from the participants, but also to build a rapport with the skaters, encouraging them to engage with later stages of the consultation process.

Following the completion of this initial consultation stage, the Council formulated two concept designs based on the information collected from the surveys and interviews. These designs were presented at a series of community workshops, attended by approximately 100 people in total. The workshops represented the diversity of the area’s population, and included a large proportion of young residents and skaters.

The workshops were centered around the question ‘What do you want the Fremantle Youth Plaza to be?’, and provided participants with information about the site and the planning process, and involved creative design exercises. Participants were asked in groups to create a design for the plaza using site models, and the outputs from these exercises were used to inform the final design of the space.

It could be argued that the popularity of the space is partly due to the Council’s willingness to rely on the future users of the plaza so heavily in the design consultation process, resulting in a space that is designed according to the wants and needs of young people in the area, rather than according to broad (and often incorrect) assumptions about what young people want. The plaza is an example of the benefits of meaningful consultation with young people in the place-making process.

This case study is one of many, and offers a model for youth engagement that we would like to see implemented across Western Sydney. The need for youth-specific public spaces in Western Sydney is evident, and a creative, inclusive approach to designing these spaces will result in the best outcomes for young people and the broader community.

––

Youth Action is the peak body for young people and youth services in NSW. They represent 1.25 million young people and the services that support them.