Beyond the sea wall: a changing climate calls for dynamic solutions

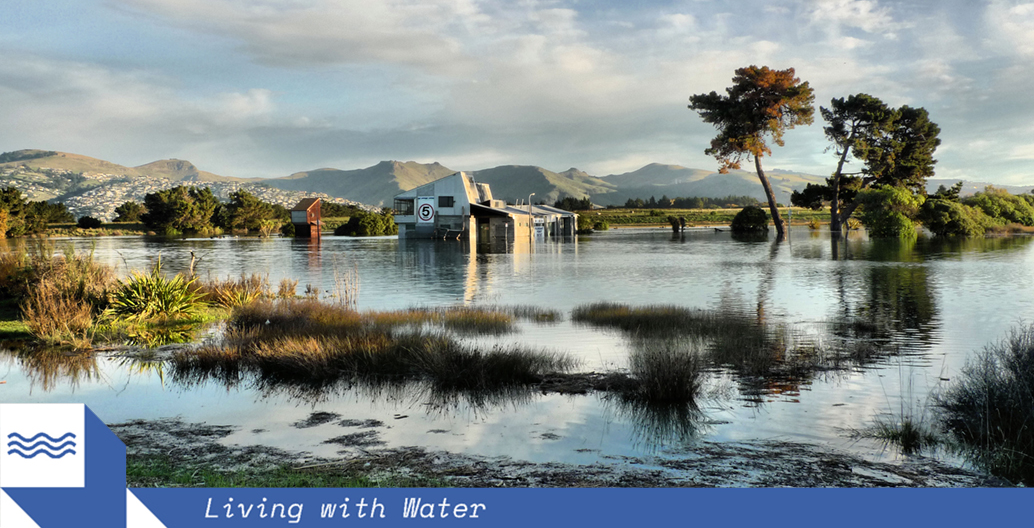

San Francisco and Christchurch may not exactly be twin cities, but when it comes to rising sea-levels and ground water, they face similar challenges – and an opportunity to rethink coastal protection.

On the face of it, it’s difficult to see similarities between the San Francisco Bay Area and Christchurch, New Zealand. The former is a major hub for one of the largest economies in the world with a population of over 7.5 million people, and home to tech giants like Apple, Google and Facebook. The latter is a gateway to Antarctica, historically a market town and port that services an agricultural hinterland, and home to just under 400,000 people. However, when landscape architect and UC Berkeley Professor Kristina Hill examines the two places through the bi-focal lenses of geology and landscape, unexpected parallels emerge.

Both places face similar challenges: how to adapt their coastal and estuarine environments to sea level rise, how to live with a high and rising ground water table, how to factor increasing salt and fresh water flooding into planning their urban environments and infrastructure while surviving, and preferably thriving, in highly active seismic zones.

Hill was in Christchurch in July 2017 to speak with communities, local and central government and share strategies for creative adaptation to sea level rise in seismic zones. Unlike the Bay Area, Christchurch has already experienced ‘the big one’ this century: a series of major earthquakes that dramatically altered the landscape of New Zealand’s second-biggest city. One of the most significant responses to its earthquakes of 2011 was the clearance of over 6000 houses on either side of the Ōtākaro Avon River between the central city and the sea. Dubbed the ‘red zone’, this land has a very high water table, prone to flooding and liquefaction, and it experienced significant lateral spread during the earthquakes. These 600 hectares are now owned by central government and provide new opportunities for adaptation to the threat of a watery future.

Sink holes and liquefaction in Avonside, now in Christchurch's red zone. Image: Martin Luff.

Sink holes and liquefaction in North New Brighton, Christchurch. Image: Martin Luff.

Christchurch's inner-suburb of Avonside now forms part of the ‘red zone’, rendered uninhabitable by the earthquake.

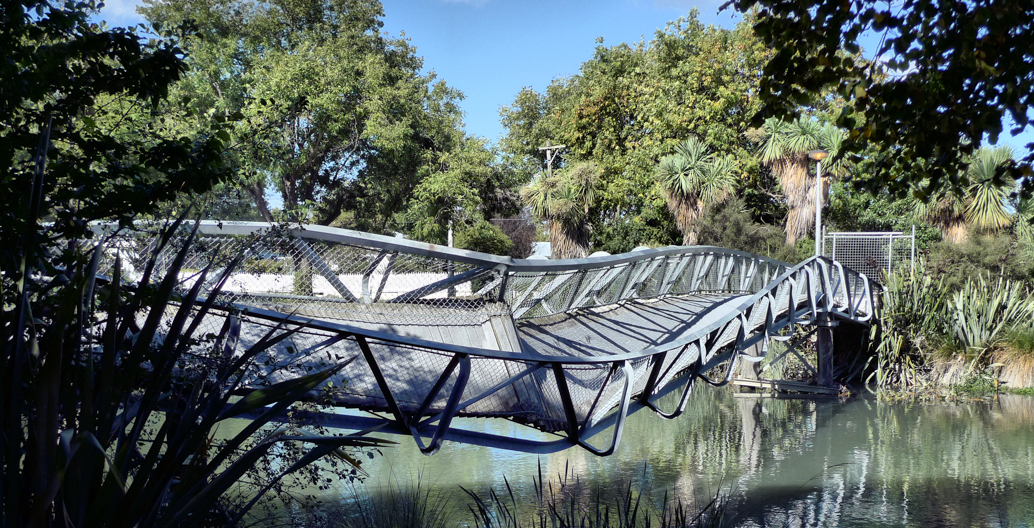

Footbridge over the Avon River dismantled after successive Christchurch earthquakes. Image: Martin Luff.

Instead of seeing this abandoned land as broken, fragile and weak, Hill recognises its capacity to be powerful. “Landscapes can be muscular, they can provide functions other than recreation and do work that supports human and other life to thrive.” She acknowledges, however, that we need to be willing to create this future by sensitively manipulating and working with the landscape’s own materials and processes.

Hill has produced an original typology of adaptation design options: a clear matrix formed of fixed or dynamic walls and fixed or dynamic landforms. Examples of fixed walls include concrete highway ‘lids’, sea walls, and floodwalls, such as New Orlean’s huge sea walls. Tide gates, movable surge barriers and temporary walls are all examples of dynamic walls, the most famous of which is probably the Thames Barrier protecting London. Fixed landforms are some of humankind’s oldest approaches for managing water: dikes and canals, levees, mounds and breakwaters, designs mastered by the Dutch over hundreds of years. The last group, dynamic landforms, contains some of the most innovative developments in adaptation design – mimicking and deploying nature’s own structures: marshes, beaches, sand dunes and bars. Hill’s typology provides a useful framework for Christchurch communities to consider the suitability of different adaptive design strategies in their local context.

Dynamic landforms hold the most attraction for Hill, especially for adapting seismically active landscapes to sea level rise and fresh water flooding. Her preference is based on solid research and reasoning. Fixed or dynamic walls or fixed landforms might be appropriate choices when facing a stable, certain future. However, when the rate and extent of sea level rise is so uncertain, how high are you going to build that wall or what volume or rate of water will that tide barrier manage? These heavily engineered or mechanical solutions are hugely expensive. The generation that builds them need to be confident that their cost will be repaid before they become obsolete and more money is required for an even bigger replacement. Their robust construction requires imported materials and expertise, which adds to their overall cost.

As Hill argues, walls not only keep water out, they separate people from the changing environments in which they live. Without being able to observe changes over time, human resilience reduces. While walls might sustain limited human habitation, they also alter ecosystems. In Christchurch, communities value the coastal plants and animals whose habitats would be eradicated by fixed seawalls. Finally, fixed solutions are at significant risk of catastrophic failure, especially in seismically active zones, where they are not only at risk of cracking or collapsing, but in places like the Bay Area and Christchurch they are also at risk in a tsunami event.

By comparison to walls and fixed landforms, dynamic landforms hold myriad social, economic and environmental benefits. They have the great advantage of being constructed using readily locally available materials: principally sand and silt. These are in abundance in Christchurch. As well as reducing immediate costs, these options are not fixed liabilities for future generations to inherit. Rather than requiring replacement these landforms are transformable by future generations, who can add or remove material and more easily alter the designed formation for new conditions. Because dynamic landforms restore and enhance natural environments, they produce improved habitats for non-human species, both plant and animal. The resulting increase in biodiversity also contributes to a higher quality of life for humans, providing an environment people want to live in. Other benefits include the creation of new recreational spaces and increased land values.

Salt wetlands or marshes typify the muscularity Hill identifies in adaptive landforms. Wave surge is one of the greatest risks of sea level rise, resulting in greater erosion and damage. Research shows that as little as a 60-metre strip of wetland can reduce storm surge by up to 75 percent. Red-zoned land fringing Christchurch’s estuary provides an ideal opportunity to test the capacity of wetlands to reduce storm-driven waves on Southshore, a vulnerable area of residential land.

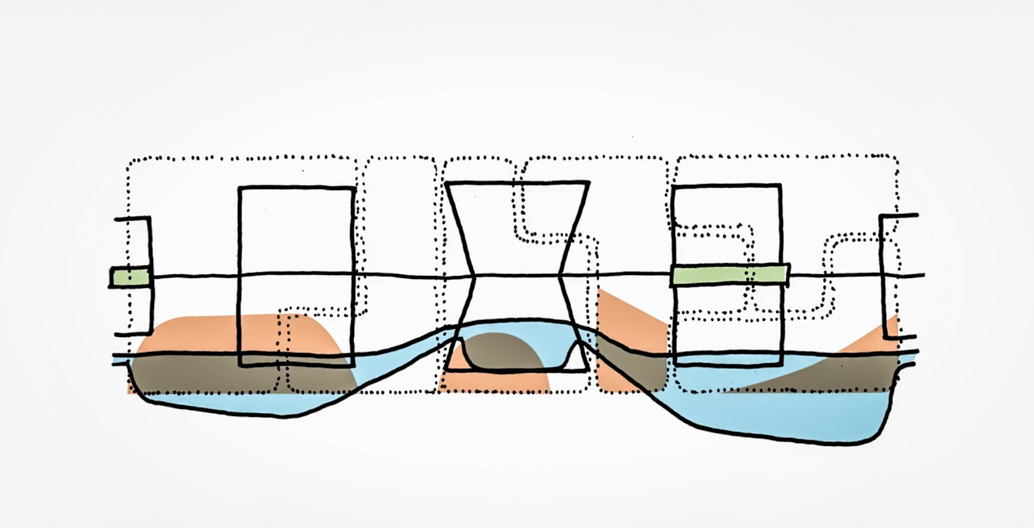

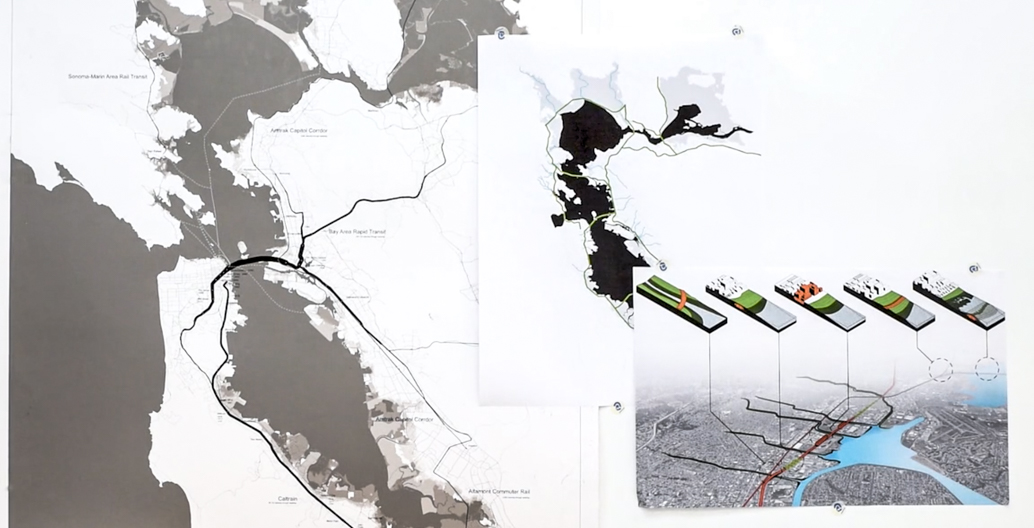

Kristina Hill's different iterations of ‘resilience’ corridors.

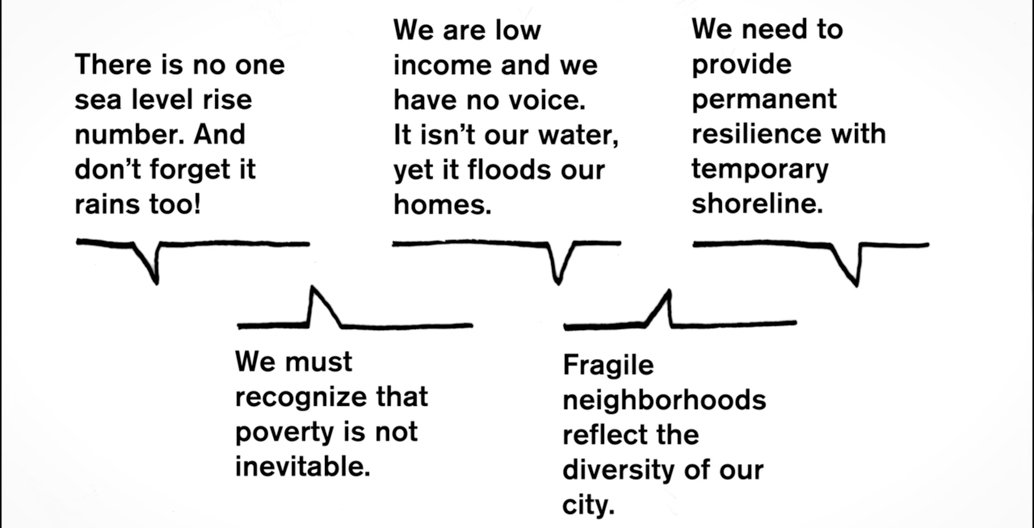

SF's All Bay Collective proposes a new resilient community forged by activist groups and residents.

Community consultation from residents sitting around SF's vulnerable flood planes.

Different typologies propose a new way to connect communities across social and geographic boundaries.

The risk of inundation also comes from fresh water sources. Rising sea levels result in a corresponding rise in fresh water tables, particularly in places like Christchurch and the Bay Area with their porous soils and high water tables. As saltwater is denser than freshwater, it infiltrates underneath freshwater, pushing it up, closer to the ground level and increasing ponding and freshwater flooding. Hill also proposes landform adaptations to manage freshwater flooding from aquifers and stormwater. Currently, all the stormwater from the northwest side of Christchurch city is channelled into the Ōtākaro Avon River. The red zone alongside the river could be adapted to clean and temporarily store stormwater. Cutting storage ponds would provide suitable material to restore this area’s original wetlands to clean the stormwater before it enters the river. The ponds would slow its release, reducing flooding in neighbouring suburbs.

Hill matches fixed and dynamic, wall and landform adaptation designs with corresponding designs for urban form, especially housing. These include examples from Germany and the Netherlands, of floodable streets and public space, floating urban blocks on pontoons and floating houses on stormwater collection ponds. In these settings people accommodate themselves to the dynamism of the environment in exchange for high-quality living on or beside water. While Hill’s arguments for using dynamic landforms make sense in Christchurch, the corresponding urban and housing forms are less relevant here for now, as density isn’t yet as pressing an issue.

Above all, Hill advocates for thoughtful, research-based design that promotes three public goods: a courage to invest in public works, greater shared resourcefulness to be able to live with change, and expanded compassion that understands the needs of diverse communities and benefits non-human species. As every nation in the world jointly faces the challenges and threats posed by climate change and sea level rise, her positive and hopeful approach is an argument in favour of landscape architecture as the design discipline best placed to lead our collective responses to this dynamic and uncertain future.

––

Dr Jessica Halliday is an architectural historian and is the co-director and co-founder of Te Pūtahi – Christchurch centre for architecture and city-making and the Festival of Transitional Architecture (FESTA).