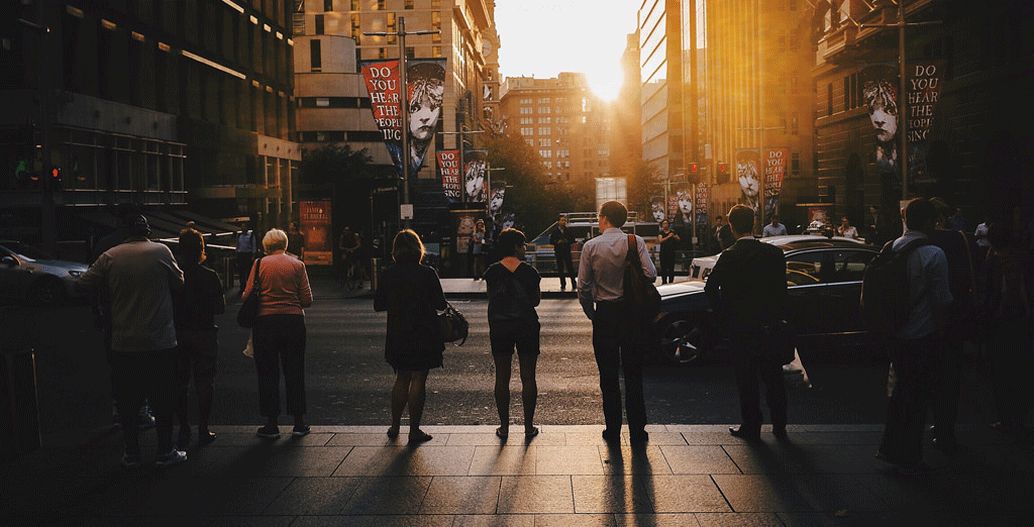

Are Australia’s cities equipped to handle its impending population boom?

Australia has been the only developed country to enjoy 26 years of economic growth, while its cities have reaped the benefits. But, as more and more people flock to the capitals, Australia’s envious quality of life is at risk.

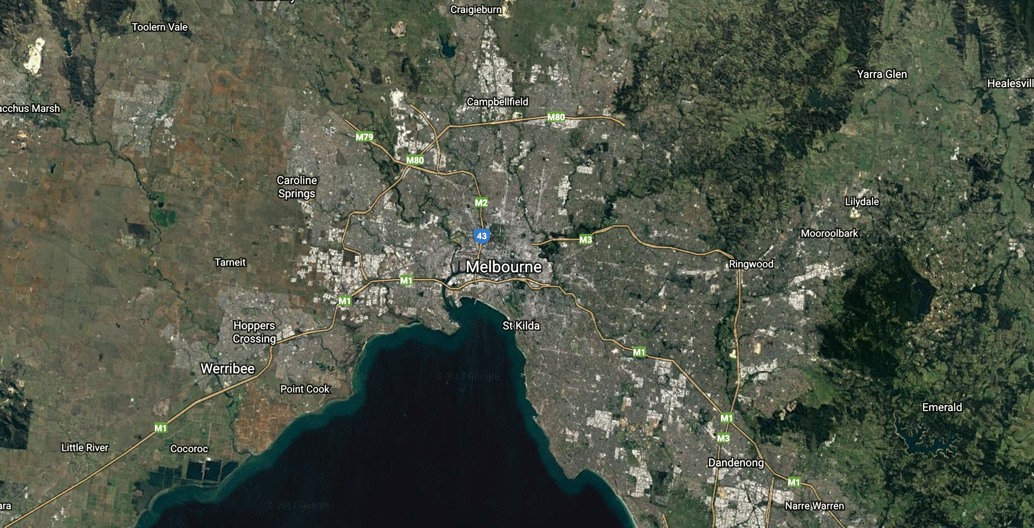

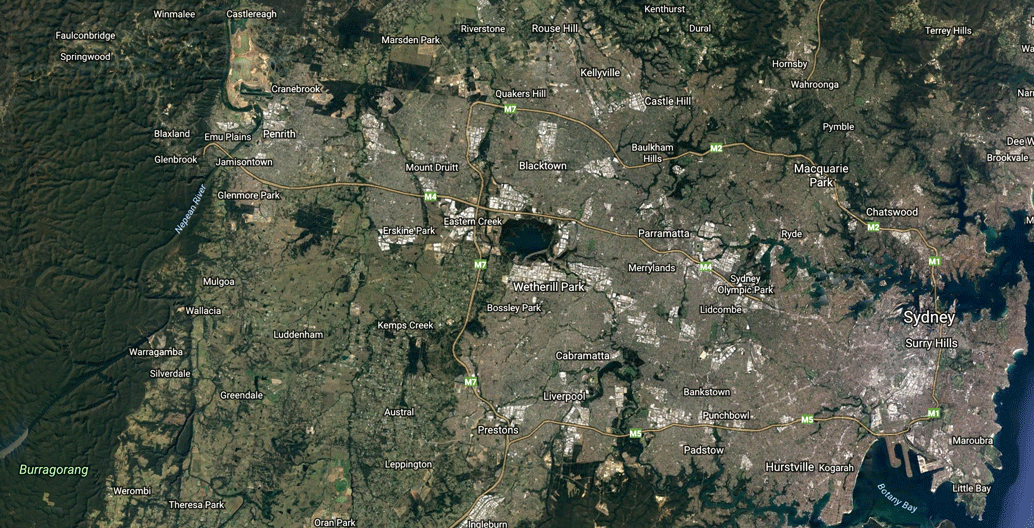

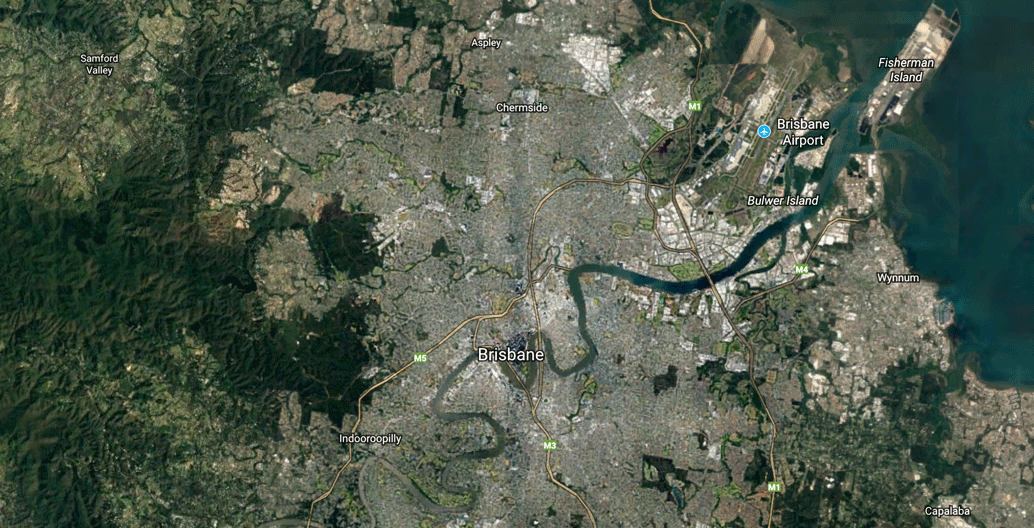

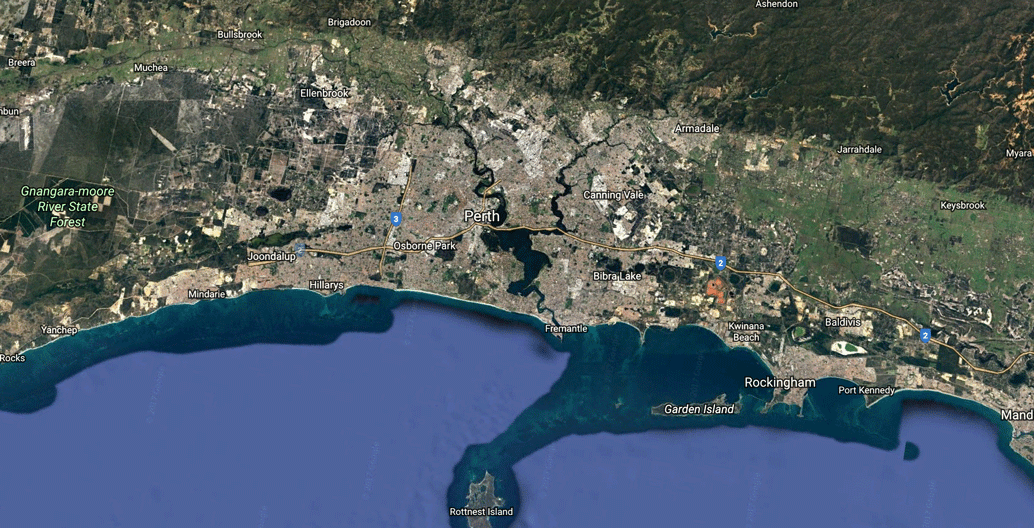

Australia has the highest rate of population growth of all the medium and large OECD countries. And more than three-quarters of the growth is in four cities: Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth. But urban planning for this growth is often inadequate.

For a start, attempts to reduce infrastructure costs and save agricultural land by imposing urban growth boundaries have foundered.

In Melbourne, the statutory urban growth boundary has repeatedly been pushed outwards. The city is struggling to meet its urban consolidation targets.

In Brisbane, a 2015 University of Queensland study found well-connected individuals own 75 percent of rezoned greenfield areas but only 12 percent of comparable land immediately outside the rezoning boundaries. The researchers conclude that rezoning was primarily driven by these landowners’ relationship networks.

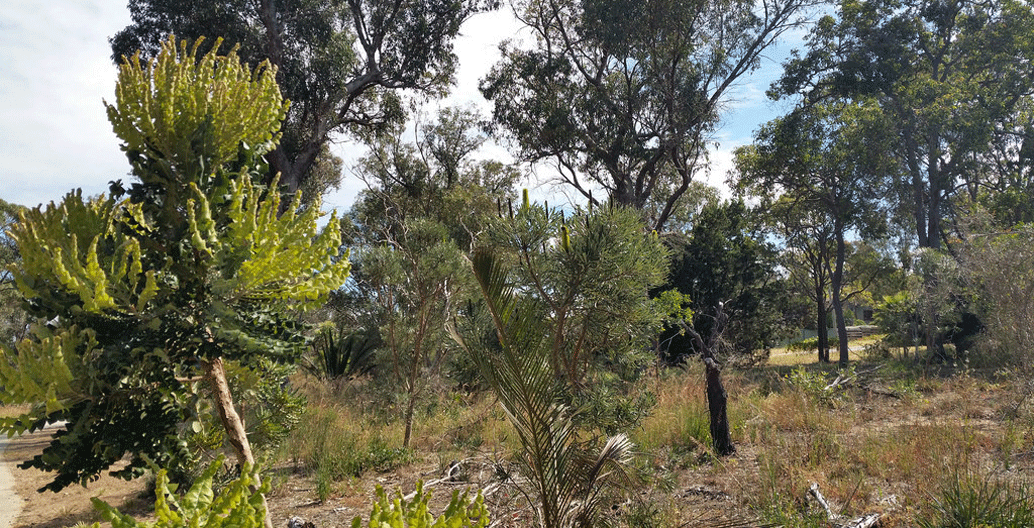

Banksia woodland, Western Australia.

The endangered Carnaby's black cockatoo. Image: Ken & Nyetta

An Koala in peri-urban habitat.

In turn, planning is failing to protect high-value environments from urban development. Policies to preserve koala habitat around Brisbane have failed. Land clearing has increased since 2009.

And in Western Australia, under Perth’s draft strategy, 50 percent of the remaining feeding habitat of the endangered Carnaby’s black cockatoo and 98 square kilometres of banksia woodland will be lost.

Despite their expanding area, Australian cities have less green open space. In attempts to reduce the costs of new infrastructure to meet the needs of increasing populations, average housing block size has been reduced.

New suburbs have virtually no backyards because the planning process has failed to mandate minimum garden areas. The result is urban heat islands that lack greenery and recreation space.

Costly housing of poorer quality

Rising populations require more infrastructure. In Australia, the developer contributions required to fund new local infrastructure are passed on to new home buyers in the form of higher house prices, reducing affordability.

Alternative methods could eliminate up-front hits on new home owners. An example is benefit assessment districts, where infrastructure is funded by bonds and repaid by the beneficiaries over decades. But state governments are resistant to this because new public loans are seen as a threat to state credit ratings.

Governments are also reluctant to use value capture, which involves applying a levy on increased property values arising from greenfield or brownfield rezoning. The levy proceeds pay for infrastructure or affordable housing.

Governments have seen such a levy as increasing developer costs and thus decreasing affordability. However, if value capture is signalled in advance, developers will reduce the price they pay for new sites to take account of the levy. In high-cost London, affordable housing targets of 35 percent have been applied to developers, compared to the 5 percent proposed for Sydney.

Furthermore, poor planning for high-density developments in Melbourne has allowed developers to meet increased population demand by constructing “vertical slums” of micro-apartments of under 50 square metres with windowless bedrooms.

Such developments are illegal in comparable world cities. A recent report found that weak planning controls have allowed Melbourne’s high-rise apartments to be built at four times the densities allowed in Hong Kong, New York and Tokyo.

Due to the supposed effects on affordability and saleability, developers are not being required to provide new open space for higher-density urban populations. In some cases, these services aren’t being funded because governments set caps on developer contributions to local infrastructure to reduce dwelling costs.

According to the Local Government NSW association, necessary state government infrastructure for higher population densities is often lacking too.

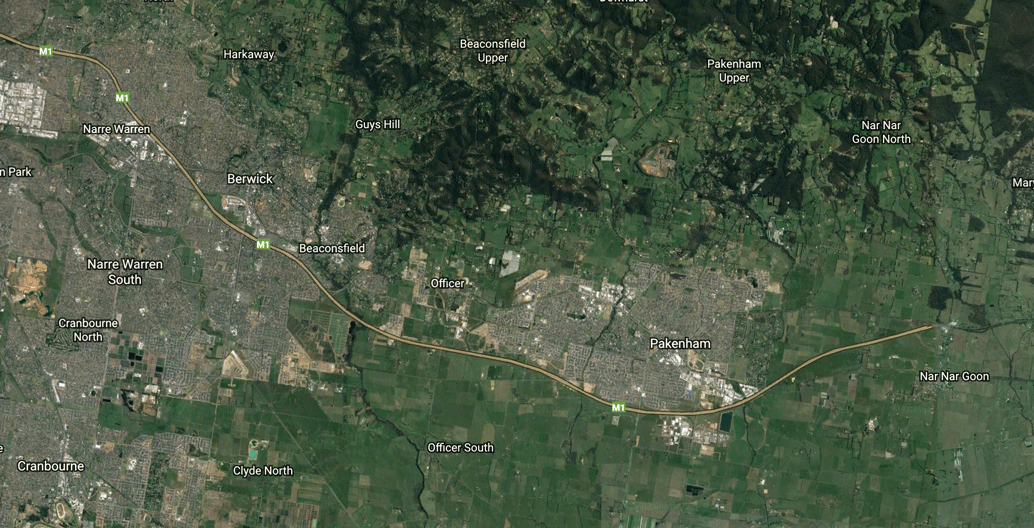

In Melbourne's far-outer-east, Pakenham sits right on the urban growth boundary.

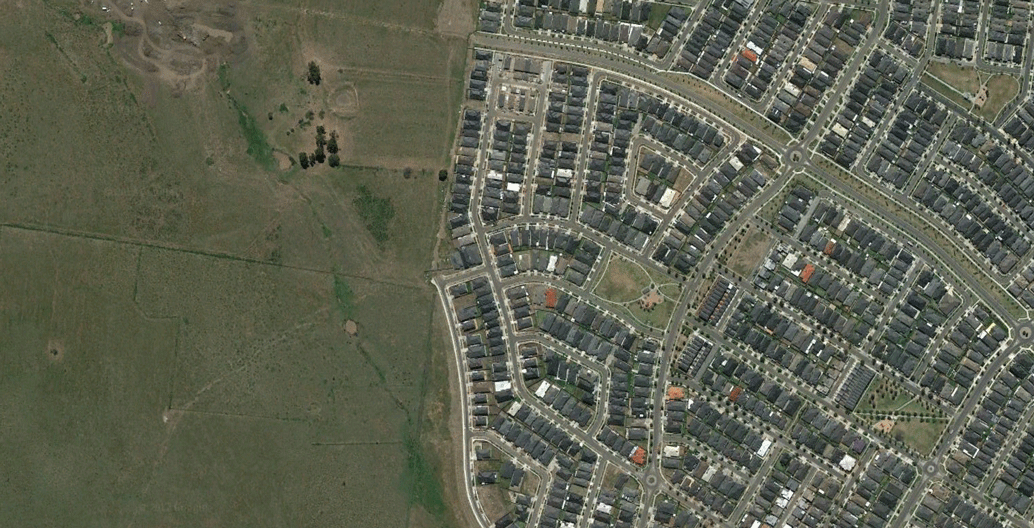

Melbourne's outer-western suburb of Wyndham Vale, where the public transport commute is an hour and a half.

Melbourne's urban growth boundary in clarity.

Sprawling Melbourne.

The drive from central Sydney to Penrith takes an hour and a half.

The river city, Brisbane, in full.

Perth looking east. Contrary to Australia's east coast, the city sprawls along the coast instead of towards the interior.

Politics of traffic

Urban population growth forecasts are driving estimates of huge increases in traffic congestion costs. However, electoral politics are also overriding pro-public transport strategies such as metro rail.

Three major motorway projects initiated during the Abbott era in Sydney, Melbourne and Fremantle cut through progressive inner-city electorates, while appealing to outer-suburban swing voters.

Inner-city motorway developments are still proceeding. WestConnex (Sydney), Western Distributor (Melbourne) and Legacy Way (Brisbane) are driving investments in private profit-making transport infrastructure. Comparable cities overseas, such as San Francisco, Toronto, Vancouver and Los Angeles, stopped building inner-city motorways years ago.

The business cases for new motorways also omit significant community costs. In the case of WestConnex, these include:

- the costs of the extra sprawl induced by longer but quicker commuting trips;

- the time and revenue costs of capturing tens of thousands of daily public transport trips; and

- loss in value of properties near to interchanges.

Deficient business cases caused four inner-city motorways – Cross City Tunnel, Lane Cove Tunnel, Clem 7 Tunnel and Airport Link – to go into receivership in the last few years, as the demand was never there.

Hostage to the Growth Machine

Part of the problem is Australia’s acute vertical fiscal imbalance.

For instance, 80 percent of Sydney’s taxes go to the Commonwealth, not the state government. This means the federal government reaps the income gains from bigger city populations, while the states lack the resources to provide adequate urban infrastructure and services for these growing populations.

Perhaps the shortcomings of planning resulting from the need to accommodate fast-growing populations could be mended with reduced growth.

But Australian cities show all the symptoms of Molotch’s notion of a Growth Machine: a large cast of actors – the development industry, property owners and many more – have a vested interest in continued rapid population growth, and lobby to keep that growth going.

—

Glen Sarle is an Associate Professor in Planning at the University of Sydney and the University of Queensland. He was previously Planning Program Director at UQ and UTS. Before academia, he held planning policy positions in the UK Department of the Environment and the NSW Departments of Development, Treasury, and Planning.

![]()