Adapting cities for sea level rise: Kristina Hill and Nigel Bertram in conversation

From streets flooded with carcinogens, to collapsing food supplies, rising seas will bring with them a raft of nasty urban problems. Nigel Bertram and Kristina Hill discuss how our cities might survive in the age of sea level rise.

The following conversation is an edited transcript from Foreground’s ‘Living with water: Design for uncertain times’ forum held as part of Melbourne Design Week at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Andrew Mackenzie: How do you manage scenarios where you show people maps about water inundation, and essentially a whole chunk of the existing city lies in this ‘water zone’?

Kristina Hill: One of the interesting aspects of US infrastructure is obviously we don’t maintain it very often. And so we expect to see failures of conventional systems. And I don’t think that other countries will see that as early as we do. But when you can no longer flush the toilet in your house and expect it to go away, people are going to want a change. There’s only so much time you can buy by replacing the pipes because foundations of buildings will begin to heave, as the water table comes up and raises the hydrostatic pressure. So there are going to be structural failures and I hope we’ll persuade a few people to be early adopters showing us how to live with a higher water table. Without a model of how we could do it differently, we’re just going to see a lot of failure.

AM: Did you Nigel, when looking at established suburbs like Elwood, have residents come running up to you saying “oh my god” when you were showing them the projections for sea level rise?

Nigel Bertram: The response to that from the community was very strong and positive. They were already fully aware and well-conversant with these issues and a highly educated, water-wise community. They’re looking for adaptation scenarios and I guess there’s a slight frustration in some parts of the community with how slow things might move. But on the other hand they also realise that there’s no silver bullet, that no big rich authority’s going to come and solve their problems for them. They have to take some responsibility and own the issue and change behaviour alongside changes to the physical realm.

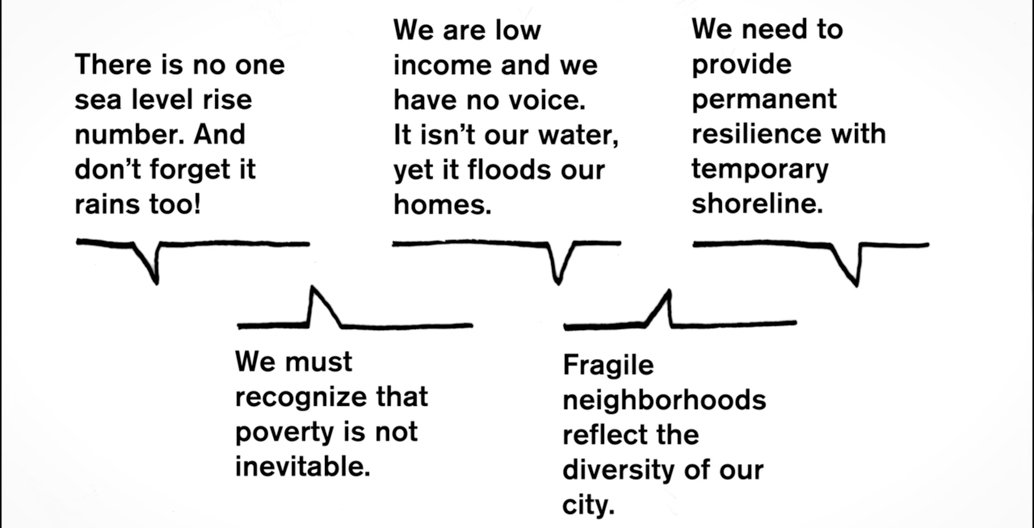

Kristina Hill’s presentation at Living with Water: Design for Uncertain Times

AM: Kristina, do you find that in San Francisco there’s a challenge in getting conversations happening between upstream and downstream communities?

KH: There is, and often in the East Bay in particular, class is stratified by position in the watershed. So wealthier people live higher up and then poor people live lower down where there was flooding and pollution from industrial activity on the Bay edge. But now there’s so much pressure to house high-income people along the Bay edge. These developments will be surrounded by lower income communities and a lot of industrial jobs, so if there’s a hint that low income people could be displaced by whatever we propose for adaptation – it stops dead in the water. That project’s not going to go forward. So we have to work the politics and economics of affordability into all of these adaptation ideas.

AM: Is there a need for conversation between professions? Because your project would need not only speak to politicians but also realtors, property people, planners and so on.

KH: Community activists, too. We’re in this competition working with community-based organisations that are low income, not particularly well educated past high school, and have a lot of grievances with the city and the county and how they’ve managed that area. So it’s hot and you have to be able to talk about race. You have to talk about class, politics, and different jurisdictions. It’s right there in front of you on the table and you have to talk about this new crisis of flooding and sea level rise.

AM: In an earlier session I raised this provocation around whether we should scare people. That section in your presentation [that shows how future flooding in San Francisco will have] carcinogens and the rubbish of the sewage pipes, that’s a scary proposition.

KH: I mean we have to be real about this too. There’s a tendency as you said to keep a lid on it. But the peer reviewed scientific research suggests that we may be dealing with between two and three metres [of sea level rise]. When people choose the central tendency number they’re not doing a service for public policy. The public sector has to consider the possibility of an extreme scenario. And even though the average person thinks, “five percent odds – that’s equivalent to zero”, that’s not true. Obviously we have to think about the potential for that scenario. And given that the estimates have gone up every year that extreme scenario has become more and more important to public policy.

Andrew Mackenzie, Nigel Bertram and Kristina Hill in conversation during our Living with water forum.

Kristina Hill wants people to “be real” about the “accelerating” risks of sea level rise.

Community consultation from residents sitting around SF's vulnerable flood planes.

NB: It was really nice to see all the historical material and the geological material in your presentation, because Melbourne has been a European settlement for only 180 years, and everything’s changed as we’ve been trying to dig it up. In the next 180 years things could change quite a lot again. Of course, sea level rise isn’t all going to come in just one big hit when we wake up, in the next century, it’s going to gradually happen…

KH: …I don’t know how gradually it’s really going to happen. I’m concerned that we are thinking about it as gradual but it’s accelerating at an exponential rate. It’s one of those things that fool people – it seems slow at first and then it starts to pick up. I try to remind everybody I talk to on the policy side in the US that we are probably in the last stable two or three decades of a 10 thousand year relatively stable environmental era. If you saw it that way what would you think? What’s the imperative? Not to sit and wait and see what someone else is going to do, but to act so your city will be competitive as all of that changes.

AM: Do we have in Melbourne the same kind of potential scenarios that Kristina speaks of, especially in relation to the industrial waste sea level rise will agitate?

NB: Well I don’t know. It’s not my area, but I do know that the current projected development projects share similarities. Arden-Macaulay, Fishermans Bend, E-gate, have high ground groundwater tables, and they’re all ex-industrial areas with contamination. So people have been trying to determine what and where it is, and the current scenario is to cap it with concrete as was described. That is not a viable solution in the long-term. Future development is completely tied up with these issues because of the desire to expand the CBD.

AM: At the start of your presentation you looked at indigenous use of land and how that was erased. Do you think there’s enough of a sufficient change in attitudes to bringing back some of that indigenous knowledge?

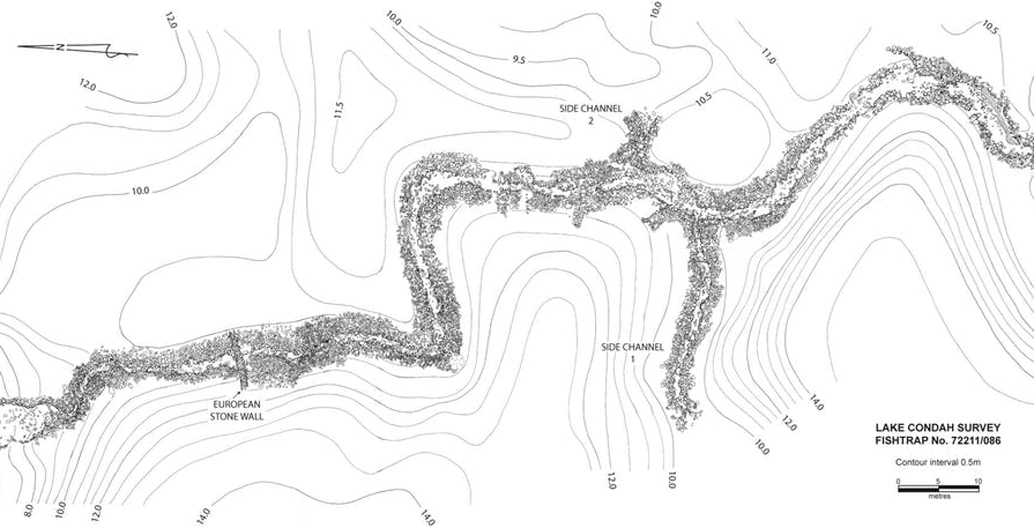

NB: We started in Elwood with an engineering flooding problem, and then it quickly became about the historical swamp, which then sprung research into the swamps and why it’s flooding. From there we went out into wider Victoria and everywhere we go where we look at a water situation, indigenous groups are strongly involved. In places like we showed at the end of my presentation, like Winton Wetlands and Lake Condah, I think they are really leading the way in planning not for the past but for the future.

Remnants of stone houses, Lake Condah. Image: Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation.

Lake Condah. Image: Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation

A 200-metre-long fish trap channel at Lake Condah mapped by Dr Peter Coutts of the Victorian Archaeological Survey.

AM: Kristina do you think this is an opportunity to think about the right scale of governance so that decisions are made where people feel empowered?

KH: Absolutely. I mean that’s one of the ways that our poorer municipalities like Oakland are stuck. There, the mayor is so busy firing successive police chiefs that she doesn’t have time to focus on this climate change adaptation question. So I think that the key thing is to find an instrument. We have one it’s called – it’s unique to California –the geologic hazard abatement district [GHAD]. So GHADs allow property owners to band together and escape local permit requirements and manage their dangerous soil conditions using their own funds. It also lets them buy into a new insurance pool statewide. So that’s what we’re talking about for these ponds that we would use this special district for people to be able to get out of most environmental restrictions and be able to do something innovative on a faster timeline which I think will attract the development community.

Nigel Bertram’s presentation at Living with Water: Design for Uncertain Times

AM: Kristina, when you started you talking about the Californian state taking land from farmers, that seemed like quite a bold thing in itself because I think everyone is now looking at productive landscapes and food security. Was that at that time a provocative thing or did the people just say we need habitat for birds over whether we need our own vegetables?

KH: It’s been provocative, but the Central Valley in California is a hundred miles away and that’s where our vegetables come from. This is mostly livestock grazing or salt ponds and the industries were not particularly economically valuable and the state acted at the right time to flat out purchase that land. It’s not a gift. It was a purchase using public funds.

AM: Is there a tension in the local context here in Melbourne between conservation and farming Nigel?

NB: Yes, but there’s also cooperation in that space. Some of the maps I showed of Koo Wee Rup picture the edge of Melbourne’s urbanised area going into the food bowl, the old swampland. And on both the Werribee side and the Koo Wee Rup side, our current city is directly interfacing with these issues and it affects not only the water performance but also the food economy of the city.

——

This conversation was made possible by the National Gallery of Victoria, the University of Melbourne, and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA).