Unmowing

“Wild” as it relates to landscape has many meanings and, as Penny Dunstan explains, even the suburban front yard can be wild and contested territory.

This is an extract from Kerb 29: Wild. Kerb is an annual design journal produced through the department of landscape architecture at RMIT University’s School of Architecture and Urban Design. Click here to order your copy.

My next-door neighbour drifts his Roundup under the fence and a little bit further. Microdroplets land on the dancing awns of Microlaena (Microlaena stipoides). He’s mixed it strong because the grass on the other side of the fence is long. That’s my grass he’s spraying.

What he doesn’t know is that the soil on both sides of the fence is sand; sand and an eon of organic matter. There is no clay to absorb the poison. It kills and keeps the area dead for almost a year. I expect he’s pleased because that’s definitely value for money.

I am sad. My remnant grassland, the tiny strip alongside my driveway, is home to many earth-others. Animals as big as quails (Coturnix ypsilophora) and as small as protozoa live there. Sometimes a coastal wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) passes through. Plants as burly as grey gum (Eucalyptus punctata) and as microscopic as algae colonise the small strip of land. Sitting in between them all are two indigenous perennial grain crops, Microlaena and kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra).

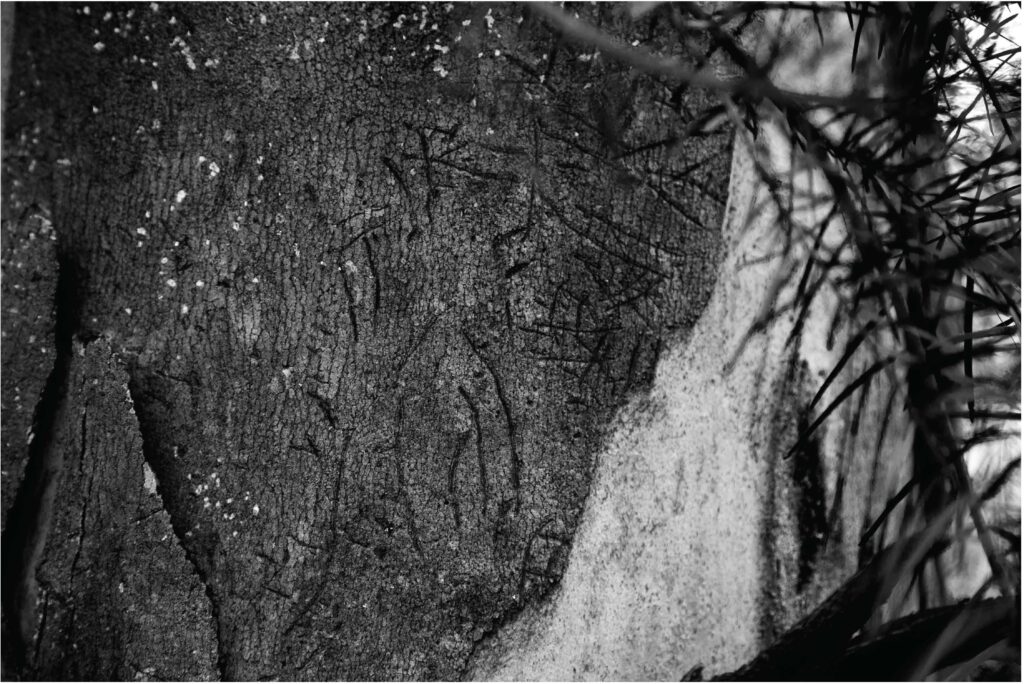

Occasionally, tucked in between the crowns of grass are ancient stones, hand-sized and smooth on one side. As I rotate a stone, I feel it snuggle into my right hand, my fingers settling in minute grooves. Women of ages past used this stone to grind the grain from the grasses that grow here to make bread. How long must a stone be used before it becomes right-handed?

This place, known to neighbours as “that untidy driveway”, has been a place of plenty for thousands of years and those stones are grindstones. Unmowing is not only untidy in the present. Unmowing crushes modern sensibilities of order and straight lines and replaces it with breathing time in Worimi Country. Unmowing unsettles colonial notions of terra nullius where lands were taken from Australia’s First Nation People. Ancient connections with those indigenous custodians spring through finger dents in stones, and indigenous grains that bend and sway in the wind. Unmowing is untidying many realms: ideas of ownership and place are contested by other beings; human, animal, vegetable and stone.

In the beginning my experiments with unmowing started by necessity. I had two small children and a full-time job. Where we lived was considered “the country”. Unmowed grass was horse feed. Saplings were future firewood. Wilderness was “bush”. Now gentrification has crept into the area. Ride-on lawn mowers have wheels instead of legs. Grass is only perfect if it is flat with manicured edges. Saplings are espaliered. And bush? Bush is somewhere else and certainly not adjacent to clean, cultivated flower beds with fashionable garden shrubs. I hold out still practicing the art of unmowing.

As Nadia Bailey says in Living with the Anthropocene: “You might see a hundred thousand trees in your lifetime, but you will only really look at a handful of them. Maybe that’s the problem. None of us are really looking.”

The grey gum is tall and magnificent, its branches home for the local magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen) troop. The practice of unmowing means it has had time and place to germinate and grow. I watched the tiny sapling struggle through the grass cover and venture into the light. Yearly growth was incremental until deep underground, tree roots found an aquifer. Within three years the tree had reached full height and began to flower feeding neighbourhood bees (Apis melifera). Seeds fell back to the soil from whence the tree was generated. I was witness to a full cycle of life: from seed to tree to seed. Now the tree is home to earth-others. Beside the magpies, small raptors use it as a lookout for the sick and elderly in my chook pen. And every year at flowering the grey gum feeds bees who make honey, which I make into mead. Unmowing has plaited me into a yearly cycle of life and plenty.

There are other flowers, too, and not all of them are native. During summer a small patch of purpletop (Vebena bonariensis) waves its flower heads over the grasses. I went to weed it out only to discover that it was being used as a halfway house by a small swarm of shiny, steel blue carpenter bees (Xylocopa bombylans). Unmowing makes the invisible lives of small things visible: it opens my eyes to seeing connections and the enjoyment of being with nature. I recall a line from Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene: “In open dialogue (with nature) one holds oneself available to be surprised, to be challenged, and to be changed”. It is my choice to move myself from the pinnacle of creation into the web of lives that surround my home. It enables me to notice the small; to be cognisant of my ability to make or break the lives of non-human others; and to insinuate myself into the myriad of goings-on in my local plant and animal community.

“You should mow your lawn.” Another neighbour registers his disappointment at my untidy driveway. It’s no use telling him about unmowing; he believes in beautiful flower beds. He plants a hedge between our properties and carefully sprays underneath so that no untidiness escapes into his yard. Unmowing is apparently contagious.

His disapproval does not dampen my joy. Today I discovered the nursery-bred grevilleas (Grevillea spp.) planted five years ago have set seed. Small plants of uncertain parentage are making their way in the spaces between the crowns of native grasses. I am excited. What size will they grow to? What colour will their flowers be? Rain has fallen and new shoots are emerging from the perennial grasses. Lorikeets (Trichoglossus moluccanus) fly in to check the nectar levels in rain-soaked flowers. The chook pen goes quiet. A small goshawk (Accipiter fasciatus) is looking for another meal: will it be bantam hen (Gallusgalus domesticus) or crested pigeon (Ocyphaps lophotes)? The pigeon loses.

Nature is an unruly process. Bearing witness is my joy.

Unmowing is an active process of practicing care that allows earth-others to set their own agendas and bring to fruition their own plans. That care is reciprocated. In Australia, these times of crisis (drought, fire, flood, mouse plague and Covid) are our reality now. Having the friendship of a tree, a familiarity of grass, or a chat with a parrot makes the world a more secure place. Unmowing is an ethic of engagement within the web of local life. It makes me curiouser, kinder, less afraid, more grateful and full of wonder at the world I live in.

This article first appeared in Kerb 29: Wild. Order your copy here.

–

Penny Dunstan is a Newcastle-based artist and agronomist/soil scientist with a specific interest in the decisions we make about land management and open cut coal mining rehabilitation. In her art practice she invites the land to represent itself through various techniques, including working with farmed topsoils and their plants, long exposure limited interference analogue photography, and a writing practice that acknowledges the old ways of Awabakal, Wonnaura and Worimi Country. She is currently represented by Curve Gallery, Newcastle.