Why streets need trees: in conversation with Libby Gallagher

Two years after launching the award-winning Cool Streets project in Sydney’s Blacktown, Libby Gallagher remains a staunch advocate for the role that street trees play in mitigating the impacts of climate change and making better cities.

FG: Let’s go back to the beginning. What drove you to become such a strong advocate for street trees, and streets more generally?

LG: I’d been in practice for close to 15 years and noticed that the street environment was the one area that was incredibly difficult to get traction in. Landscape architects were producing great ideas, but most decisions were made based on engineering criteria related to vehicular traffic, so it was death by a thousand cuts and those ideas were slowly whittled away. I wanted to find ways to re-evaluate the role of these environments within our cities, economically, environmentally and socially. Over the last decade there’s been a real push back against the idea that functional requirements are the only driver for streetscape design. Streets are deeply social spaces. But despite there being a growing discussion about sustainability in street environments, there has been no metrics to measure it.

FG: You have conducted research on retro-fitting suburban streets to mitigate the impacts of climate change and rising temperatures. How did that research enable you to produce those metrics for evaluating street environments?

LG: I undertook detailed climate modelling related to all the components of the street – materials, finishes, street layouts – in order to find out what a sustainable street would look like. The result was a prioritising of tree planting, providing more green infrastructure and minimising hard surfaces where possible. It was also about challenging preconceived ideas about aesthetics and thinking about more diverse, eclectic responses to streetscape environments.

FG: What drove your choice of Blacktown as a location to run the Cool Streets pilot project?

LG: I was interested in Western Sydney because it’s very vulnerable to climate change and increased urban heat. Unlike older inner urban areas with established trees, many of those newer neighbourhoods have largely been clear-felled, so there’s very little existing tree stock left. Obviously affluent neighbourhoods with large established leafy trees are incredibly expensive. There’s an underlying economic condition that is rarely talked about, which is that people who live in these environments are often from a different demographic group to those from areas such as Blacktown. How can we engage with those communities? During my research tree managers in Blacktown told me that it was difficult to plant established trees because local residents didn’t like them. I thought, “Is that true? What’s underlying that?”

FG: Were you able to unpack those perceptions? What was behind that difficulty?

LG: For that particular street the concerns were mainly around mess. Residents initially preferenced small trees. When we dug deeper we found it had nothing to do with size. People were concerned about leaf litter and mess. As soon as we addressed that by suggesting larger species with less leaf drop, or where we said, would you be more open to this if there was increased street sweeping during the leaf drop periods? They said, “absolutely!”

Many of the residents were also first generation migrants, who were very house proud. Simple things like positioning was important. Rather than slavishly adhering to six-metre tree spacing, we proposed allowing a slight shift in spacing for those residents, so they could see their front door. This was important. There were subtleties to the response, which might be very different in other communities. That’s why a staged process is important. It allows us, and councils, to take the time required to truly understand community feedback and ensure a meaningful outcome.

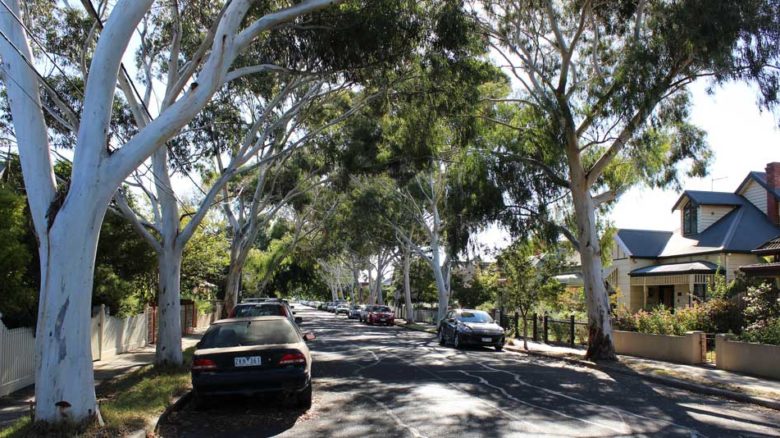

Bigger is better for street trees, but how to convince residents? Image: Philip Mallis, Flickr cc

Newer residential developments often suffer from a lack of trees. Image: Philip Mallis, Flickr cc

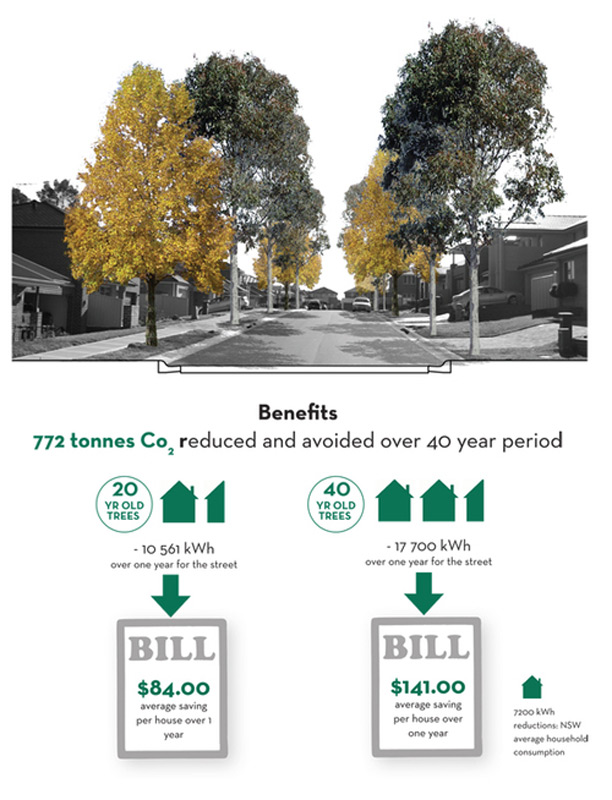

Cool Streets both gathered and shared information about tree benefits. Image: Sarah Reilly

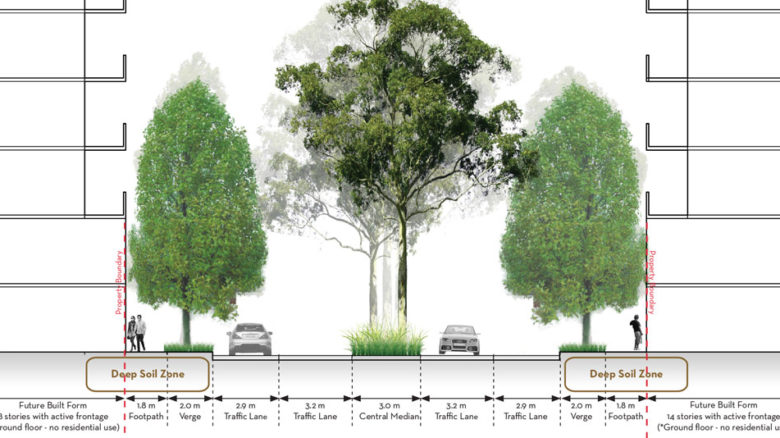

Cool Streets second stage showed design options & their benefits. Image: Allison Sainty

FG: You’ve been back to Boonderoo Avenue in Blacktown since the project was installed. What have you noticed and how are people now relating to their street?

LG: We’ve noticed that the bonds in that community have strengthened. Tree growth is also very good. There was one tree that didn’t survive, but as soon as it went into decline we were notified, everyone was aware of it! It seems like certain people evolve and become the champions for the street. I remember one resident who wasn’t particularly vocal during the engagement process, said that one of the things he loved about the project was the ability to choose with his neighbours the right tree for their street. He ended up taking care of a couple of the trees down the length of street. He’s become the the cool streets steward. The project, it seems, has attuned people into looking after their trees, which are outside their gardens and part of the public space.

FG: The “Cool Streets Method” is central to your approach. Can you explain why is it important?

LG: We worked closely with social planner Sarah Reilly at Cred Consulting to craft that strategy, which we first used in the pilot project. It’s a collaborative consultation method formed around two stages. The first stage was about information gathering and sharing, which helped us lay aside our own preconceived ideas and try to understand people’s likes, their dislikes, and why. We shared detailed information about people’s preferences, pointing out the benefits around certain species, citing things like energy bill reductions and Co2 emission reductions. We asked them, with this multiple range of benefits, would you change your preference? The process allowed a dialogue to open up, which had a clear set of options, but allowed people to crystallise their thinking and to delve deeper into their preferences.

In stage two we went back with design options, where we said “here’s what you collectively told us last time. Here are some options about what you could do next”, and we again allowed them to choose. As a designer, the process is about listening, treating the community as a core stakeholder and a client, to understand what they want to achieve, what their concerns are. From this we then developed a design response. This project is more than a tree planting strategy. It’s a process of empowering residents to make the right choice for their street, and enabling people to meet each other on the street. This factor is critical in building resilience. It provides people with a sense of “this is something that I can do”.

Environmental issues can seem monumental and overwhelming. But if you give people an opportunity to engage with something at their front door, suddenly they feel empowered to start making a positive difference.

FG: Let’s talk about your work for the City of Sydney. How did working within the dense urban neighbourhood of Green Square differ?

LG: We undertook a study looking at improving landscape quality in Green Square. We were thinking about how to provide good landscape outcomes in these rapidly evolving, medium density neighbourhoods, for both the public and private domain. We had to work within the constraints of existing planning controls, finding ways to get better outcomes for the neighbourhood as a whole, by thinking about public and private conditions in concert.

Often public and private sites are seen in isolation, because the planning and management of those sites are often segregated. In NSW in particular, there’s a focus on the importance of deep soil – the capacity to have an area on a private development site that has access to unimpeded soil depths, which allow for large trees to be established. We looked at the benefits for an apartment dweller on their lot, as well as the wider public benefits, to show where to position that deep soil to produce the best outcome. We also looked at how to make the best use of the street reserve, which have the capacity for larger trees, through careful design negotiation.

I drew on my experience working on the SEPP 65 apartment design review panels, which uncovered the factors that can make a difference in achieving better outcomes through private development, without undermining the capacity to have density on those sites. That’s one of the critical things about that work – acknowledging that we need density in our urban environments. We can’t continue to sprawl. Ultimately this is about working with planning mechanisms, to improve landscape in the public and private domain, to contribute to an improved neighbourhood for everybody.

At Green Square, Gallagher worked within existing planning controls. Image: Allison Sainty

Gallagher advocates for street designs that prioritise environmental and social function. Image: Supplied

FG: What does a sustainable street look like?

LG: Bigger trees are better. Small trees have very little capacity to achieve much in terms of reducing C02 and providing shade, so you have to focus on the larger species. Australian native species are drought resistant, they’re fast growing and they can be carbon sinks. Depending on the species, the shade provision can be akin to a deciduous tree. Some gums trees can provide winter sun and some summer shade. They can be particularly useful because they’re fast growing so they can be effective in environments sooner.

But it’s not just about trees, it’s about designing our streets for environmental function. It’s coming back to the core parameters that we’re designing our streets for. For the later half of the 20th century, street design was heavily based on vehicular movements, and had nothing to do with social function or aesthetics. If we’re looking at increased density in urban areas, there’s natural pressure on private land, so the public domain has to work much harder, environmentally. We need to make sure our priorities are right. Should we always prioritise the garbage truck, or the need for telecommunication companies to have their own service dock under the street?

There are simple mechanisms that we can use to open up new opportunities for increased tree canopies and increased landscape for environmental function, such as allowing for water sustainable urban design approaches, which need space. My research is about counter-balancing the narrow scope that we’ve had on functional requirements, to say let’s make sure we’re not forgetting all these other things. Through considered design we can help address some of the fundamental challenges our cities are facing.

FG: How well are we doing on that front?

LG: We’re starting to see big discussions about tree canopies and green infrastructure. In NSW, the Government Architects Office’s Greener Places policy has started to put it on the wider political agenda. There is now a much more engaged discussion around the importance of trees. The reception to Cool Streets, from residents and the wider public contacting us directly, has been encouraging. People have been asking “how can we get this to happen on our street?”

FG: Are there more Cool Streets on the agenda?

LG: There are additional projects being installed in Schofields, which is a new neighbourhood in Blacktown. We’ve also been engaged by a council in Victoria to work on two streets there. There’s interest and enthusiasm in the project coming from across across the country, so we’re hoping for more cool streets to come!