How did the America’s Cup instigate Perth’s green sand dunes?

The America’s Cup gave the world the winged keel. For Perth, it’s the reason why its northern reaches are replete with green sand dunes.

Perth’s metropolitan landscape shows the disproportionate and lasting influence of a long line of entrepreneurial investor-developers. Beginning with founding Western Australian Governor James Stirling in 1829, these enterprising visionaries show a complex web of motivations for their speculations. There are surprising parallels between Stirling and another investor-developer, also originating from the UK. The late Alan Bond masterfully brought together sandgroper lifestyle, Mediterranean themes and frontier swagger as he launched from the late 1960s perhaps the most extensive series of land openings in Perth since Stirling’s in the 1830s.

And all in the name of a yacht race.

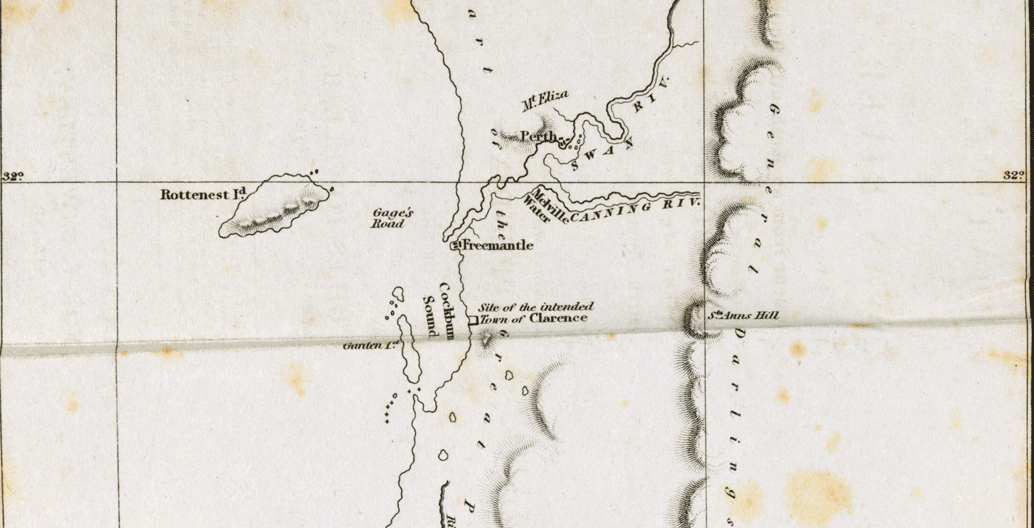

The fact that these men were both British is interesting and relevant; that they were both seafaring is especially so. Royal Navy officer Stirling’s living legacy is the pastoral colony planted along the fertile banks of the Swan River network, extending from Fremantle to Guildford. As a corporate entrepreneur and sailor, Bond’s lesser-known imprint is the extraordinary opening up and consolidation of a coastal suburbia hemming Perth’s metropolitan beaches from Yanchep to Fremantle. If Stirling’s contribution was to stake out, within the first decade of European settlement, the eastern limits of Perth’s metropolis towards the Darling Scarp, Bond’s was to extend this north-westward. Together they had prepared the ground for instrumental planning initiatives such as the 1963 Metropolitan Region Scheme and the 1970 Corridor Plan for Perth; the latter underwrote the expansion of Perth’s suburban blanket as far north as the proposed Sun City.

James Stirling. Image: Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House.

'Swan River, 50 miles up', J Huggins (1829). Image: National Gallery of Australia.

'Panorama of the Swan River Settlement', J E Curry (1830). Image: Mitchell Library, SLNSW

The narrative of a voyage to the Swan River by J. Giles Powell (1831). Image: National Library of Australia.

Bond’s speculative development of a chain of village-like marinas deserves study not only because of the significant part they played in urbanising the coast, but also for their interesting typological amalgams. Mixed in almost equal parts are the scale of British seaside towns, material form of Mediterranean villages and flatness of Perth’s suburbia.

Join us on a round trip to consider the special agency of Bond. A man who, via the prestigious and lucrative America’s Cup yacht race, instigated what has since become a virtually continuous stretch of Mediterranean green coastal sub-urbanism associated with leisure and sponsored by tourism.

Before and after

Bookending the tour are two of Bond’s major, though not entirely successful, business ventures at Yanchep and Scarborough, both envisaged during the binge on massive profits made from two America’s Cup challenges, a decade apart. We begin and end at Scarborough, Perth’s original beachfront holiday, and later entertainment, district. From here we will take a drive north on Marmion Avenue, one of Perth’s major arterial roads, to see the unfolding narrative of the city’s stretched-out coastal suburbia.

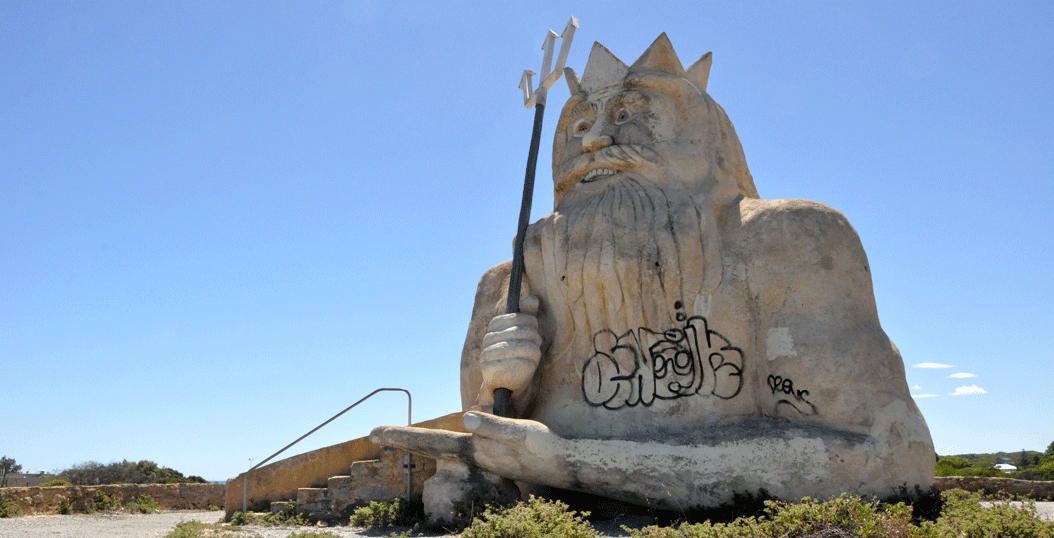

At the Scarborough end of Marmion Avenue, Bond’s Rendezvous Observation City tower complex by Robert Cann & Associates has sat forlornly since 1986, anticipating the strip development that Bond promised but could never deliver. About an hour’s drive away in Two Rocks, Yanchep Sun City anchors the northern end. On approach to Yanchep, veer off Marmion Avenue and leave your car at the ‘city’ centre to see the sites on foot – there should be an abundance of free bays if you just follow Enterprise Avenue to its terminus beneath the shadow of a giant, hollow limestone King Neptune.

Neptune and his accomplices are relics of the once-busy Atlantis Marine Park (now home to Atlantis Beach Sales Office); a souvenir of Bond’s early entrepreneurial activity along this coastal fringe, complete with Corinthian columns and frolicking dolphins (who were eventually relocated to Hillarys Underwater World). Sun City emerged after the acquisition of nearly 20,000 acres of land by Bond Corp in 1969, and marks the beginnings of his now fabled efforts, over two decades, to vie for the coveted America’s Cup. As Sun City was being slated as Perth’s next premier tourist resort and coastal subdivision, Bond was preparing for a second Cup challenge in the marina he built there.

Rendezvous Observation City pictured in 2017.

Perth, the natural home for an Atlantis-inspired theme park....

... and gargoyle-like creatures more commonly associated with medieval France.

Using the yacht race as a promotional vehicle to support the lucrative housing venture that had begun to take shape, Bond’s Yanchep is just the first of a number of coastal nodes that emerged during the fever pitch of the America’s Cup events, which we pass heading south on Marmion Avenue. These include the over-scaled and heavily privatised Mindarie Quays, begun in 1986, and the more southern Hillarys Marina, completed in time for the 1987 defence in Fremantle, with its predicted influx of tourism.

The suburbs that occupy the hinterland of these two later marinas, through which we now inexorably travel, emerged at the height of the derided and pejoratively labelled ‘McMansion’ phase of suburbanisation. These places rely not so much on the tourist-geared marina for regular amenity than on the regional shopping centre, where the drive-thru burger and orthodontic clinic are collected into one convenient monolith.

When your back doorstep is your backyard marina.

The greatest view: Toward more McMansions perhaps?

Bond's Perth, where atlantis awaits.

Suburban enterprise: The business of leisure

Bond’s early Cup forays and marina developments coincided with the implementation of the state government’s Corridor Plan of 1970. With it came Whitford City – a shopping centre gazetted as its own suburb in 1971. In 1984 its developer went on to jointly develop with Bond his namesake tower (now 108 St Georges Terrace). When it opened, Whitfords was the largest regional shopping centre in the northern suburbs, and is currently undergoing major redevelopment.

As you drive by the suburban streets, they rattle off the names of colonial explorers who opened up the rest of the country for European exploitation: Padbury, Dawes, Baxter, Eyre, Forrest and countless others identify the cul-de-sacs, crescents, closes and loops of Perth’s northern garden suburbs.

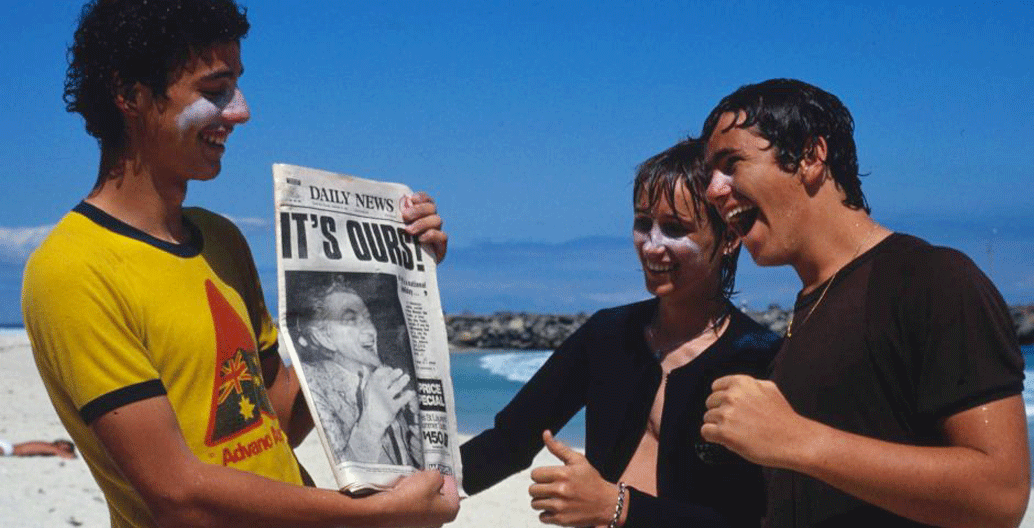

If Bond’s genius was in recognising the business potential of the Cup, it goes without saying that this alignment with suburban sensibilities was an integral part of his public character and marketing strategy. In Newport, Rhode Island, where the Yanchep-funded challenge took place, Bond, with his vast quantity of Australian beer in tow, warned the champagne and gin-and-tonic traditionalists of the American yachting world that the days of this being a gentleman’s sport were long gone. This rhetoric meshes persuasively with the coastal suburbia Bond was promoting in his enterprising housing subdivisions: leisure of this (12-metre yachting) kind was not only available to aristocrats or gentlemen, but accessible to what was then considered the ‘ordinary’ middle-class, suburban, home-owning, mortgage-reliant Australian.

Sun City: Greening the sand

Bond’s brand of urbanism is a curious mutation of Stirling’s original garden-and-cottage vision. The Governor’s early recommendation of the name Hesperia (after the mythical Garden of the Hesperides) for the Swan River Colony had intended to capture its aesthetic, but also economic, potential as a place for British settlers. As the ‘land looking west’, its geographic position was ideal for trade, the climate and fertile soils were suitable for agriculture, and the flatly undulating grass land promised the idyllic pastoral lifestyle. But Stirling had focused inwards, upon the riverine landscape. By contrast, Bond was drawn to the beach. Unable, however, to make living on a sandy windswept dune site attractive to the local market, Bond had the Yanchep dunes painted green to add garden suburb appeal.

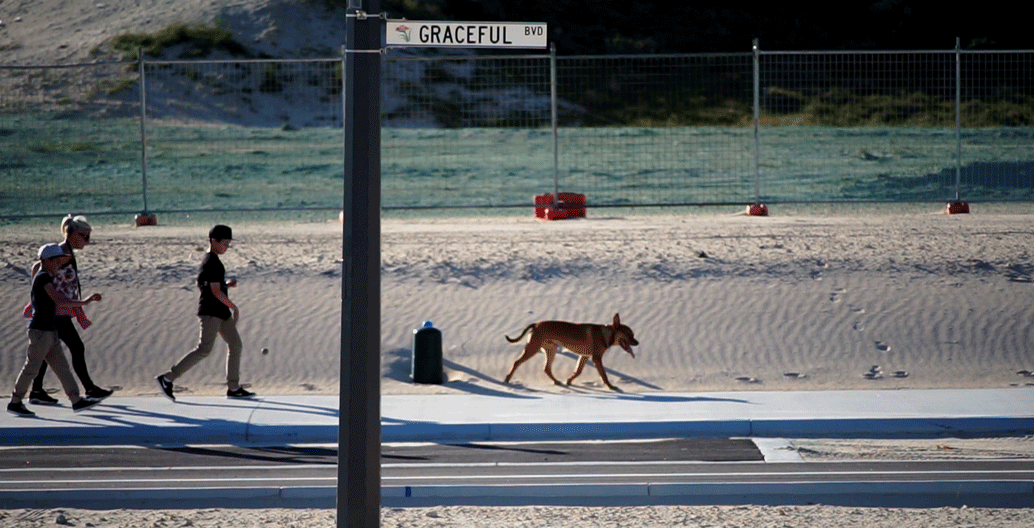

It remains to be seen what will happen to many of these now-abandoned theme park and coastal sites. The most likely outcome is the equally absurd extension of the dominant contemporary subdivision that attempts to plant English gardens on dune landscapes while simultaneously evoking the language of urban sophistication. It is possible to live in your ‘Manhattan’-styled three-bedroom home, enjoy a morning flat white by the lake and then take a stroll down Graceful Boulevard for a late-afternoon surf.

In the context of Australian urbanism the garden suburb is well documented. Unique to Perth, though, is this evocation of the Mediterranean and its correspondence with the marketability of leisure. Let’s go back to Sun City’s town centre for a moment and consider the quality architectural manifestation set out by architects Forbes and Fitzhardinge in 1975. A cluster of beige village-like forms, constructed from brick, the centre’s toggled corners recall the masonry tectonics of a Venetian structure perched somewhere along the Cretan coast, while the blue and white paint detail might evoke memories from that sailing holiday you once took through the Greek islands.

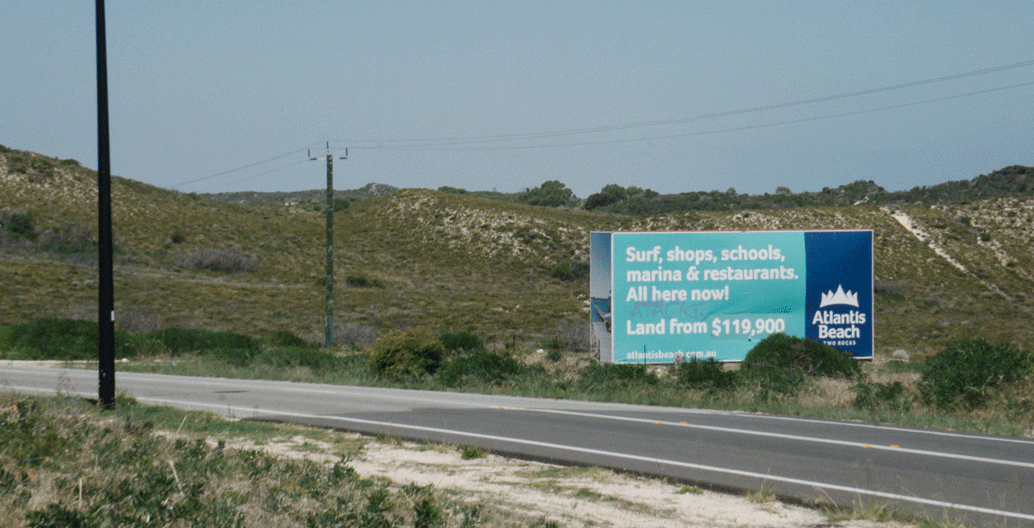

But just as Bond’s original scheme for the city folded, Forbes and Fitzhardinge’s town centre and the remains of Atlantis are appearing more like an archaeological site than a bustling village. Having originally overestimated the market potential, Bond sold out his interest to a multi-billion-dollar Japanese corporation which, after waiting for Perth’s property market to catch up, proceeded to resuscitate the housing enterprise and continue to develop the region at an extravagant pace. In place of the pedestrian alleys of the local plateia, however, new commercial centres feature up-scaled big-box retail and Toyota SUVs.

Is this the legacy of a "idyllic pastoral lifestyle"?

A pint by the yacht bay? Welcome to northern Perth's suburbia.

A pleasure dome by the marina.

A community park with a view.

Enjoy a morning flat white by the lake and then take a stroll down Graceful Boulevard. Image: Felix Joensson

Scarborough fair?

Yanchep now inevitably awaits its northward extension, pushing the bookend of our tour another hour’s drive up the coast. There, at Lancelin, one can observe the awkward mingling of the cray fisherman’s fibro beach shack with the ‘Florentine limestone’ brick and grey Colorbond-encircled catalogue homes. Lancelin has, since 1986, achieved notoriety for a grand windsurfing race that attracts competitors from all over, decent surf and the shifting sand dunes that loom somewhat precariously over the township.

This freshest subdivision, Lancelin South – Quality Coastal Living, markets an “enviable holiday lifestyle” and adopts the windsurfing motif and the catchphrase ‘set sail’. Another example of seafaring suburbanism promoting and propped up by the business of leisure.

The green hills of northern Perth's sand dunes?

Bond’s Rendezvous Observation City with new development.

Closing the tour, back at our starting point, Rendezvous Observation City no longer stands alone. Though Bond’s initial plans here were stymied by a local institution – the kebab shop Peter’s by the Sea, who wouldn’t sell – his influence remains tangible as the Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority (MRA) adopts one of his old tricks: the green dune. Another has emerged. This is the most recent, but certainly not the last, in a fascinating series of projects ‘greening’ Perth’s metropolitan beaches. Sunset Hill is the aptly named, westward-looking grassy knoll that now foregrounds the Rendezvous.

Thanks to the MRA’s massive investment in the foreshore redevelopment new apartment buildings have sprouted in the last year. The collocation here of quintessential beach culture, major transport thoroughfare, corporate prowess and an up-to-the-minute mixed-use higher-density lifestyle-guaranteed coastal redevelopment makes it a magnetic hub. Capping it all: a just-announced, 40-storey twisting twin tower proposal by Hillam Architects for Chinese developers 3 Oceans Property. The developers’ managing director, Dyno Zhang, taking some wind out of Bond’s sails, remarked to The West Australian: “It’s so important we provide a legacy for the future and look at how we can create social capital.”

––

This article has emerged from work on a forthcoming website project called ExcursionsWA, which has been funded by UWA’s Centre for Education Futures. The first part of this project is due for completion in September 2017.

This article first appeared in Future West, a biannual publication that addresses the need for a conscientious debate about architecture, planning, culture, and society across Western Australia and beyond. It looks towards the future of urbanism, taking Perth and Western Australia as its reference point.