New infrastructure performance measures for Australian cities questioned

The federal government has updated the National Cities Performance Framework Dashboard. The infrastructure performance indicators seek to measure infrastructure and investment needs but how helpful are they? What do the new measures mean for our understanding of urban transport and happiness?

The only reason to move anywhere is to be near something, far from something, or possess something. Location is about proximity. People make location decisions all the time, from whether to move from North America to Australia, to whether to go to the mall by car or bus, to whether to stand near this or that person at a reception, or even whether to sit on the chair or the couch. Businesses do likewise, from deciding where to build a factory and where to locate a store, to which shelf to put the Pepsi to maximize profits.

The underlying logic of all these decisions is the same, despite the difference in scale, timeframe, motivation, and mode of travel. People and organizations will pay a premium to be in locations with higher accessibility to the things (people, opportunities) they care about, to save time (spend less cost in travel), and to be more productive (earn more), all else being equal.

The number of jobs reachable within 30 minutes is perhaps the most widely used proxy for urban accessibility. This number is a measure for cities for several reasons. First, the `number of jobs’ is a surrogate for `urban opportunities’. People work at their jobs, and job locations are places of interaction that provide service either directly or indirectly to customers. Next, being `reachable’ is a function of land use (i.e. how close and dense things are), as well as how fast people can move using different modes of transport. Finally, `30 minutes’ is a typical one-way travel time budget, and the national average for commuters in Australia is 33 minutes.

The Australian Government should be applauded for their efforts in benchmarking cities in terms of transport performance in the recent National Cities Performance Framework. While we are delighted to see the government include this 30-minute access to jobs benchmark for the first time, we have significant concerns about how the framework applies it.

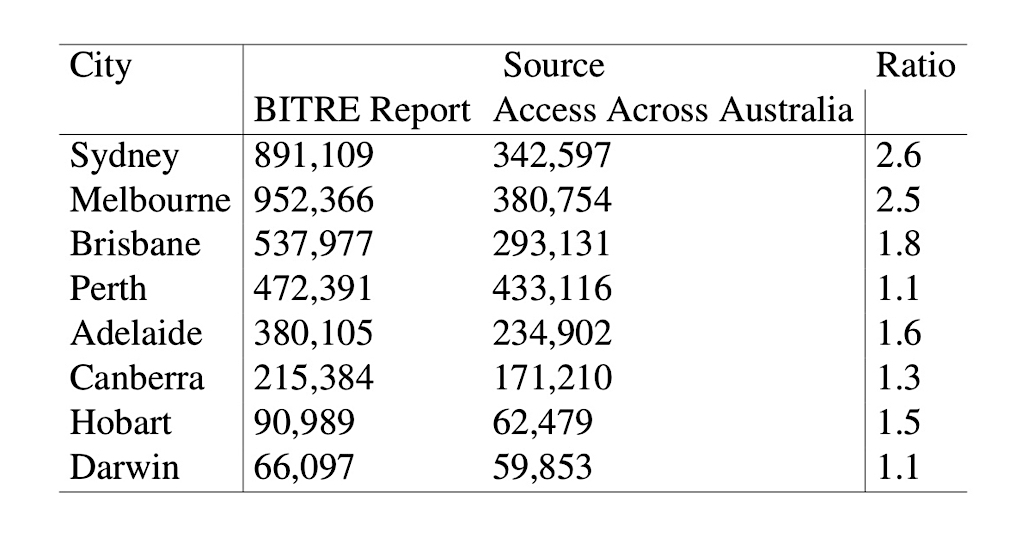

First we have trouble with the actual numbers within the framework, as they differ widely from what we and others have computed. The morning peak car access measurement appears dubious. The city-level access is measured by first sub-dividing the city into zones, then averaging the access to jobs from each zone to produce the city-level averages. If the car access measurements from the Australian government framework were correct, then Sydney and Melbourne would have become perhaps the world’s most accessible automobile cities for their sizes, based on our assessment of eight Australian cities. The framework uses data from the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE) that calculates average automobile access to jobs in Sydney at more than twice the number of our own calculation, and higher than even the most accessible suburbs based on a report prepared for the Committee for Sydney.

The reason people are in large cities is not to reach a percentage of jobs, but to reach actual jobs

Second, we have trouble with some of the metrics the report uses. Interpreting access as valuable, measured purely by the `proportion of jobs accessible’ within 30 minutes is misleading. Obviously small cities will find all residents can reach their small number of jobs, but in large cities they can’t. This means little. The nominal value of jobs accessible explains land value, commute duration, mode choice, and many other socio-economic variables. A higher percentage of local jobs reachable doesn’t translate these cities into economically more attractive places. The use of `proportion of jobs’ penalizes cities that are larger, but with more jobs present. As we can see from the report, larger cities have an inversely smaller proportion of jobs reachable; this makes the `proportion of jobs accessible’ an uninformative indicator. The reason people are in large cities is not to reach a percentage of jobs, but to reach actual jobs.

Third, a fully fledged access measure would include the number of jobs accessible by walking, biking, and public transport, as well as by car. While the framework measures the proportion of journeys made to work by public and active transport, there are no measures of the number of jobs that are actually accessible by these modes. For example, our study finds that Melbourne has better car access to jobs than Sydney, but Sydney has better transit access. This information cannot be found within the BITRE framework, which distorts the accessibility picture. Active modes of transport are a vital part of urbanity. Measuring pedestrian access sheds light on the convenience of city centres, and bike access outperforms public transport in many cases, which supports arguments for infrastructure such as protected bike lanes to improve biking safety and rider comfort. It is disappointing that only access by automobile is included in this report, despite the high public transport mode share in major Australian cities.

The initiative by the Australian government to include accessibility measures is very much appreciated. In fact, very few governments in the world have computed access to jobs measured nationally. We look forward to BITRE updating their numbers with input from experienced analysts as Australia progresses toward better performance measures of the land use and transport infrastructure of our cities.

–

Prof. David Levinson joined the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Sydney in 2017 as Foundation Professor in Transport Engineering. He conducts research on accessibility, transport economics, transport network evolution, and transport and land use interaction. He is the Founding Editor of Transport Findings and the Journal of Transport and Land Use and author of several books including: The Transportation Experience, Planning for Place and Plexus, Elements of Access, and The End of Traffic and the Future of Access. He blogs at http://transportist.org

Hao Wu is a PhD candidate at the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Sydney and a graduate of the Georgia Institute of Technology. Wu’s research interest is accessibility and related transportation and land-use issues. He works on measures of accessibility under the supervision of Prof. David Levinson.