A tale of three Sydneys

Presenting at this year’s Planning Institute of Australia congress, the CEO of the Greater Sydney Commission Sarah Hill set out the Commission’s plans for the years ahead. Foreground caught up with Hill to talk about Sydney’s western expansion.

Foreground: Last year, the Commission unveiled its “three city vision” for a polycentric Greater Sydney, with six draft District Plans. This appears to have a strong strategic logic from a planning perspective, but what are the “pull factors” – what will convince a person or company to put down roots far from Sydney’s historic and vibrant heart?

Sarah Hill: It is important to first note that the western parts of our city have large amounts of land that are currently already zoned for residential development. There is still a lot of capacity within the existing zoned areas. Part of the reason why people are currently not moving to those areas is fundamentally related to jobs. People are choosing lifestyles that allow them to live close to their work and reduce their commute time, to the extent that it is affordable to do so. The game-changer for the west therefore is around attracting the kind of jobs that a growing population will need.

Alongside this there is also the need to improve amenity and reinvigorate the west as a desirable place to live. That means improving the environment, entertainment venues, cafes and a range of urban resources that can make it a real city, rather than just a suburb.

FG: You mention the city and the suburbs. Australia’s urban fabric has historically been highly predicated on fixed divisions between these two. In planning for future urban growth, is there a need to rethink the binary of city and suburbs?

SH: The truth of the matter is that cities are dynamic and they evolve all the time. While our planning timeframe is 40 years, we can’t bring static 1960s thinking to urban growth over that time. Technology is a part of that dynamic mix, as are lifestyle preferences and expectations.

As strategic city planners we need to balance three different forces. Firstly, we need to protect and preserve things that we love. Secondly, we need to safeguard the things that we can change, not right now. Some things can be held on to for future opportunities. Thirdly, we must rethink and change some things that we are doing now.

Heritage is very important to us, and will become increasingly so, but that doesn’t mean it can’t adapt, sensitively. The capacity to protect our heritage, while adapting the city for future needs, relies on trust. Building trust with communities is an important part of what the Commission needs to do.

Formerly the seat of NSW governors, Old Government House now sits in a booming Western Sydney. Image: Chris Loutfy.

A triangular forecast of Sydney's growth.

Emerging skylines in the City of Parramatta. Image: Chris Loutfy

FG: In conversations about funding future infrastructure, the term value-capture has recently become very popular. What are your views on how to approach the funding of infrastructure?

SH: As a Commission we work in collaboration with the Department of Planning and Environment, Transport for NSW and Treasury. Our role is to help bring a better understanding of what infrastructure we will need and when, and then to do the homework on where the gap is between what we have and what we need to fund and finance. While the responsibility for implementing such mechanisms as value-capture and development contributions lies with the Department of Planning, it is something the Commission is very aware of.

For instance, when considering a new train line, it’s not just about trains. It’s also about aligning transport with new schools and health resources, and all sorts of other infrastructure that is needed, which comes off the back of growth. We will soon be looking at a precinct-based approach to what we need. So, our key input is to identify the where, when and how. Then we work with government agencies whose job it is to explore funding and finance models to make it work.

FG: You work across all levels of government. Is that hard when they often don’t see eye to eye?

SH: Yes, an important aspect of the Commission’s role is to collaborate with the three levels of government, to make sure they are all working well together. At a local and state level we see ourselves as the glue in a land-use sense, helping to bring all the necessary elements together. Importantly, from a planning point of view, the Commission has a mandate to look at the long-term needs of the city.

FG: This points to a common frustration with government, whose three-year cycle often seems to drive short-term solutions. How do we break this cycle of short-terms needs compromising long-term needs?

SH: The Commission has been established as an independent entity. It approves District Plans for Greater Sydney, which inform Local Environment Plans. So, on the one hand, that takes district planning decisions away from the politicians. However, given the power we have in that sense, we work very closely with local government to make sure those District Plans make sense. That capacity to think at the large scale, embedded within an understanding of local issues and concerns, and to do so as an independent Commission, is important for our capacity to plan for beyond the expediency of immediate needs.

FG: Would you say that your relationship with local government is in fact more important that your relationship with federal government?

SH: I cannot over-estimate how important our relationship with local government is. We don’t want to step on their toes. We want to give them the information, evidence and support they need. That said, we also need to take the bigger picture view and make a call for Sydney. In recognising that there are 28 local councils, we need to make sure they all work together for collective outcomes.

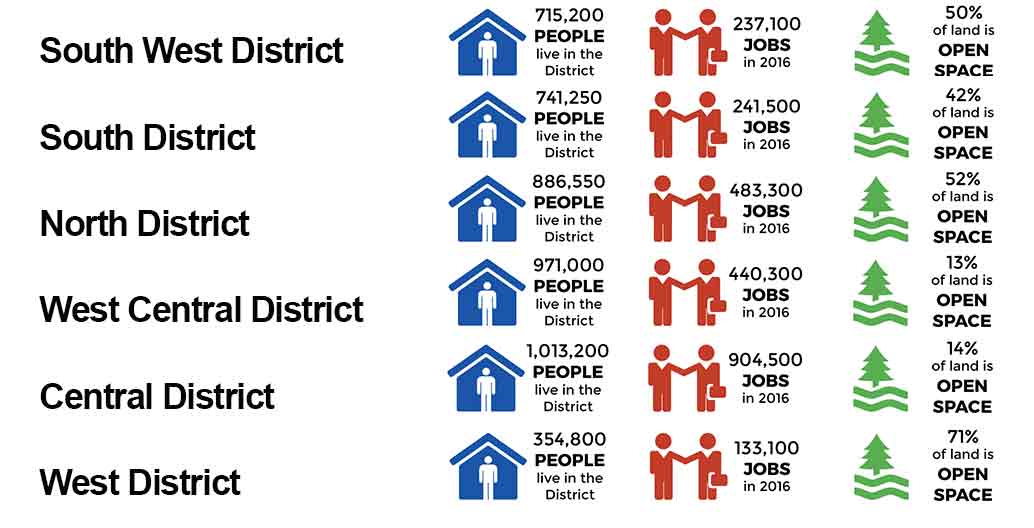

A demographic snapshot of Sydney's six districts as defined by the commission.

The six districts mapped.

FG: Returning to rail, how would you rate the NSW report card on implementing better integration between transport needs, and housing and job needs?

SH: I think we have that kind of integration happening all over Sydney. Look at St Leonards, Chatswood, Parramatta, Auburn. Yes, we can do more in those areas, and we will. The development around the Sydney Metro Northwest stations is forward-thinking in that regard. And yes, we need to look at other areas that are completely undercooked from a transport sense.

Interestingly, much of the tension that used to attend increased urban densities around train stations has largely dissipated. A lot of communities recognise that growth has to go somewhere and I’m really pleased that communities are now recognising that there are options and trade-offs. So increasingly, I find they are getting comfortable with density around stations, which allows other areas to be maintained or protected with a lower density.

FG: Given the inevitable impact of ‘smart city’ technologies on your strategic plans, to what extent can those plans be future-proofed? Are you listening to people who sit outside of the conventional disciplinary boundaries of planning?

SH: We are absolutely listening to those outside of the planning profession. Our Chief Commissioner Lucy Turnbull is incredibly passionate about the influence of technology on our streets, and our plans will speak very strongly to that. But the truth is, we don’t have a crystal ball. There are things that will happen in the next 10 years that none of us at this planning congress are yet aware of. So we need to prepare plans that are resilient to technology changes. We need plans that can be regularly adapted to changing circumstances.

For instance, everyone is talking about driverless cars. Personally, I go back and forth on how much that will change things. On the other hand, some of the big changes that might happen may have their roots in simpler technological improvements, such as in signalling for instance. The way we gather information around the city is also important, to better understand how it operates. Simple mechanisms to measure how effective open spaces are, in terms of their utilisation across the day, might also influence how we plan and grow our cities.

Fundamentally however, our plans have to be about people. About their changing lifestyles, their choices and preferences. The technology side is important, but a lot has to be said for the simple things that most people want: being able to get together, to socialise, to share resources, to walk more to stay healthy. And everyone likes to be able to look at a tree!